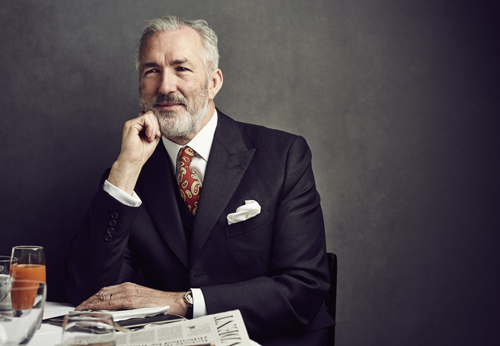

The Caterer interview: The Wolseley founder Jeremy King on his hospitality philosophy

Since opening Le Caprice in 1981 with long-term business partner Chris Corbin, Jeremy King has been behind some of the most iconic restaurants to open in the capital in the past 35 years. He spoke to Amanda Afiya at The Caterer Summit, and explained his hospitality philosophy and what was behind the recent rapid growth of Corbin & King. Emily Clark listened in

You and Chris Corbin are two of the most highly regarded operators in the industry and you've inspired generations of restaurateurs. Did you consciously set out to be leaders in the field?

I don't think it's that we set out to be leaders. In fact, for most of my working life, I've been looking up for people to act as mentors. Then somebody very kind said to me: "It's about time you started looking down instead of looking up, because people are looking to you for leadership."

Why do you think you've made such an impressive and imitated mark on the industry?

As far as restaurants are concerned, we have maintained a very simple ethos of opening establishments that we'd like to go to and hope that people will enjoy. We treat people as we would like to be treated. I still often find it very hard to concede, though I'm 61, that people might be looking up to me.

Is press and social media something you've reluctantly embraced?

We appointed a PR many years ago â" the very accomplished Martine de Geus â" and for about four years she sat on her hands because it was defensive PR rather than open. The transformation came when we opened Brasserie Zédel, which was a very large restaurant that needed to appeal to a very broad range of people.

I like to use the word narrowcast rather than broadcast. Itâs getting to the people who you actually want to come to your restaurant rather than telling the whole world. What Iâd want the papers to say is that âso and so were seen at the Wolseley having breakfastâ. Other people, curious intellects, will say âwhatâs the Wolseley?â and theyâll find out.

We all know you for opening Le Caprice in 1981, before going on to open the Ivy and J Sheekey, and then selling the business to open the Wolseley. What do you put that success down to?

Weâve always considered ourselves restaurateurs rather than restaurant owners; hoteliers rather than hotel owners. And what I mean by that is that restaurateurs roll up their sleeves, they get their hands dirty, they are seen in their restaurants every day. The single most important factor is that, during those years, we actually owned 100% of Caprice holdings. It had to be an organic growth.

Who supported the Wolseley?

We were looking at the new project which would need funding, and I was asked by a banker what my perfect investor profile was. I suggested a deaf-mute Australian with a fear of flying â" he said that might be tricky.

We were not prolific; we opened one restaurant every eight years. The Wolseley happened because it was offered to us in a conversation with David Coffer in a hotel. It was what we had dreamt of, a grand café. At that point we were getting older â" when we opened Le Caprice I was 27, with the Wolseley I was nearly 50.

We couldnât do one only every eight years, we needed some backing to accelerate. That was in many ways the biggest mistake we ever made; we perhaps didnât back ourselves enough. We entered into that world of co-ownership, which can be tricky. Luckily, it has settled down now and we are in a good partnership.

Is there one particular restaurant or hotel that has given you more pressure or that you feel more sentimental about?

I suppose my analogy would be asking a parent which was their favourite child. Itâs important that I love them all, but itâs that one that youâre with at that moment. I might be standing in the Delaunay at pre-theatre with its buzz, or it might be later in the evening and the bandâs struck up in Zédel, and there are 200 people in the room. At that moment, thatâs the one that gets a disproportionate amount of love.

Thereâs a real sense of tradition throughout the restaurants and the hotel. How do you embrace new tastes while maintaining that?

Our industry is one of the most reactionary you could hope for. Time and time again Iâve been questioned by staff, asking if we really need to take on new technology, why everything canât stay normal. I remember putting up a big sign saying âchange is normalâ.

I was doing an induction this week. The new staff asked me questions and one of them asked what book I was reading. It happened that I was reading a book by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, set in Sicily, that contains a famous line that I think is appropriate for our business: âIf everything is going to stay the same, everything must changeâ.

We are making subtle changes and improvements all the time, but they are perhaps barely discernible to the customer. What I adamantly do not want to do is follow the latest trends; we are in this business for the long term and are not interested in flash-in-the pan notoriety.

The Beaumont

Is that your philosophy towards change and leadership?

Iâll give you an example. Ten people discuss some new innovation in the business â" the one at the moment is bill sharing through credit card technology. I said to them I was really interested in what they had to say, but I couldnât promise that I would take their advice. That is the nature of leadership and Iâm a great believer in autonomy, autocracy â"Â perhaps even benign dictatorship.

The precedent I can remember is a group telling me we wouldnât need computers, voicemail, EPoS, any of these things. Theyâve all been decried. Itâs about keeping things the same â" a sense that people know where they stand as a customer â" but using all the technology to enhance the ability to look after them.

You and Chris always come across as gentlemen, and it feels as though thereâs a gentle hand on the tiller. Meanwhile, your chief operating officer Zuleika Fennell comes from an HR background. Does that mean there is a lightness of touch within the business?

The phrase âhuman resourcesâ makes me think of Soylent Green, the film about humans being fed to humans in order to keep going, so we call it âpersonnel and developmentâ.

When you look at the restaurant business, there is no greater cost than our personnel. We spend more on the staff than food and drink combined, and three or four times more than rent â" and they were given so little consideration. But I think the industryâs changed a great deal in that regard.

Leika runs that side of the business from the floor â" the biggest plight of our industry is that decisions are made from the boardroom rather than from the floor. It is an easy decision to cut 10%. On the floor, looking that staff member in the eye, who youâre going to cut as part of your 10%, itâs a very different thing.

Having said that, we are demanding a certain standard of performance and itâs really important to us that we donât carry any passengers. That might make us ruthless in some way, but itâs ruthless in a pursuit of excellence rather than a pursuit of profit.

Whatâs wrong with pursuing profit?

The moment staff see someone walking through the door of a restaurant or a hotel as a source of income, the business is really doomed. That changes your attitude, because it gives your a business finite life. You have to look at people walking through the door as an opportunity to give somebody a good time. If you give them a good time, then you make money.

You find hotels with an average daily rate of £1,000 and they still charge £15 for Wi-Fi. Itâs an insult and itâs purely because the financial director is pushing the profit line; thereâs no vision about it.

Brasserie Zédel

Thereâs a lot of talk about a staff shortage. Do you think itâs worse now than it has been?

I think the quality of staff is much higher. When Chris and I came into the business, we still had the hangover from the time when Britain thought that if your idiot son didnât work hard, he would go and work in the kitchen. We didnât even call it a profession; we looked at the people who cooked in kitchens as a sub-species.

That was breathtakingly changed by a lot of the pioneers. I looked to people like Simon Hopkinson and Alistair Little, who showed that there was room for a great deal of intelligence in the kitchen.

We tended to think it was only the Italians and the French who could really give service professionally. The ability to advance through the restaurant business now makes it a fantastic career. Would I have allowed my child into the industry in the 1980s? Probably not. Now, definitely.

Do you think people can see those opportunities now? The perception is that wages are very low.

And theyâd be right â" the massive challenge we have at the moment is wages. For a long time we at Corbin & King have been working off a maxim that chefs should be paid a proper wage, working five straight shifts a week. I lost nine chefs at Delaunay at one point, and they were all being offered 40%-45% more salary elsewhere. They discovered that they had to work nine or 10 shifts a week.

In April 2016, when we have to change to the living wage, just the hourly rates will cost us £850,000. By the time we establish the cost for those earning above the threshold, it would be £1m. Most of that money will go to people who are earning three or four times the minimum wage anyway, because we are not allowed to take into consideration the amount of tips the front-of-house staff are earning.

Nobody should ever be on the minimum wage. Weâve already got 90% of employees well above the minimum wage for 2020, but that doesnât mean people shouldnât earn more. If we include service charge into the bill as opposed to voluntary service charge, that would get better distribution among the staff, but then we would lose 20% of the service to VAT, on top of the NIC implications. There would actually be less money going to staff. We need our professional associations to stop hiding behind the parapet and speak out a bit more.

Have you come up with a solution?

Nobody seems to have. We need help, we need the Government to understand the challenges facing us. There needs to be less of a desire to increase taxation, and more of a desire to improve conditions.

At the moment, the only way that we can make this work is by putting our prices up in a market which is already overheated. But thereâs no point lifting up your banner and striding into battle when you realise that nobodyâs following you.

Whatâs the property market like now? You must be a victim of your own success trying to snap up other sites.

Itâs a happy problem. We tend to like local restaurants now and the first thing that happens is that the agent tells everybody else that weâre interested, which whips up the price more.

Iâve got to the point now that I canât be aggressive in the market. I said all along I only want landlords who want us. As it happens, we have a lot of state landlords â" Grosvenor, Cadogan, Howard de Walden, the Crown â" and they have a greater vision for whatâs needed, rather than maximising the rent and increasing the value of the building. It is very hard, so any hotel we do we would want control of. It has to be on a management contract basis, which the hotel business has moved towards strongly.

Will you open any more hotels?

The problem is, everybodyâs trying to open a hotel at the moment and the prices have gone up. Iâm fascinated by it; I love the hotel business because Iâm trying to buck the trend and I long to open more hotels.

You have shunned dynamic revenue management, instead focusing on a more predictable room rate for guests. Why?

You can go into a big hotel in January and get a room for £350, which would cost you £750 in May and £950 in June. Our guests return because they know what they will pay. The strength of our industry is on loyalty â" itâs so much easier when people come back.

The night before last we were full at the Beaumont and 45% of the people were returning guests. You see it in airlines; everyone is doing yield management, which is terrorising the business and there is no loyalty. What would restaurant guests think if the price of a steak varied according to demand?

Whatâs your idea of good hospitality?

When greeting people, any gratuitous questions should be cut out. Too much of our business these days is about going through the motions. I want to walk into a hotel where somebody has Googled me, sees I have travelled from San Francisco, and says: âHello Mr King, welcome to the Beaumont. Now I see youâve had a long journey, I expect youâd like to go in your room straightaway rather than being shown around. Would you like a cup of tea or a coffee?â That, for me, is hospitality.

Corbin & King

Jeremy King was working at Joe Allenâs when he met Chris Corbin in the late 1970s. In 1981, the pair acquired Le Caprice and built the business up before opening the Ivy in 1990. The restaurant was an enormous hit, topping the Zagat and Hardenâs guides regularly and becoming the place to eat in London.

Corbin & King continued to restore faded restaurants with the renovation of J Sheekey in 1998. That year, Caprice Holdings Limited was sold to Signature Restaurants, with Corbin & King staying on as non-executive directors until 2002.

The pair returned to the restaurant scene with the acquisition of the Wolseley in 2003. After many successful years running the all-day brasserie, the pair went into overdrive, opening the Delaunay in Londonâs Aldwych in December 2011, Brasserie Zédel in Sherwood Street in June 2012, Colbert on Sloane Square in October 2012, and Fischerâs on Marylebone High Street in spring 2014.

Their first hotel, the Beaumont in Mayfair, opened in September 2014, before their latest restaurant, Bellanger in Islington, opened at the end of last year.

Bellanger

The latest Corbin & King restaurant opened in Londonâs Islington in December. Bellanger takes its name from the pairâs tradition of linking restaurant names to cars, with this one inspired by Société des Automobiles Bellanger Frères, a French car manufacturer from 1912 to 1925.

The 200-seater restaurant is designed by Shayne Brady, who designed Fischerâs and the Delaunay, Brasserie Zédel and Colbert under David Collins.

The menu has a distinct nod to the Alsatian routes of the original Parisian brasseries, with food served from early breakfasts to late dinners. Dishes include a range of tartes flambées, sharing dishes such as coq au Reisling, along with a range of escalopes and sausages, and main courses such as calfâs liver with black bacon and sage, and cod à la Grenobloise with lemon, capers and parsley.

The head chef is Lee Ward and Claire OâSullivan is the general manager.

Â

Â