Crapaudine beetroot cooked slowly in beef fat recipe

At the Michelin-starred Black Swan in Oldstead, North Yorkshire, beetroot takes centre stage in head chef Tommy Banks' multi-textured dish

Beetroot's dominant trait is its colour, which is why so many chefs use it to spice up their presentation. Grown as micro-veg it makes a pretty garnish, and combined with two-toned Chioggia or golden beet it has an even stronger visual impact.

In current use it tends to be an add-on, with few chefs rising to the challenge of making it the focus of a dish. Heston Blumenthal used beetroot to make what looked and tasted like a blackcurrant pastille, but only in its altered state as a visual joke. Aside from the classic East European borscht, recipes designed to highlight beetroot are thin on the ground.

Given this back seat role in kitchens, it's little wonder Crapaudine beetroot isn't a mainstream variety. The name comes from the French for toad (crapaud) and refers to its thick, rough skin. It's large, weighing up to 500g, and will keep all year if stored properly in soil or straw.

Crapaudine beetroot is never off the 14- course tasting menu at the family-owned Black Swan restaurant with rooms in Oldstead, North Yorkshire. Head chef Tommy Banks discovered it via Northumberland plant breeder Ken Holland, who recommended it for its flavour (extra sweet, especially after storage). The restaurant is part of the family farm near Thirsk and Banks' father Tom now grows a 20-tonne crop to guarantee supply.

Slow-cooked in beef dripping and served like a wedge of pie, it has little in common with the familiar boiled or baked beetroot. In both taste and texture it's a radical new addition to the culinary repertoire. It hasn't been transformed or deconstructed, but is at once recognisable as beetroot.

Planning

For the dish, Banks uses a smoked, glazed wedge of Crapaudine beetroot as a base, and tops it with pickled discs of golden and red beetroot, horseradish goat's curd, smoked cod's roe emulsion and linseed crackers.

- At the Black Swan preparing and cooking batches of Crapaudine beetroot is done daily and takes 4-5 hours. It is held at about 55°C during service.

- Using the trimmings to make the glaze is done in larger quantities, usually 4.5kg, which reduces to about 500g of finished glaze.

- Pickling beetroot discs involves sealing them under vacuum for at least an hour as part of the mise en place.

- The smoked cod's roe emulsion and the horseradish goat's cheese curd are prepared daily.

- Linseed crackers will store for several days in a sealed container.

The kitchen makes about 30 portions of beetroot ahead of service. For the photography Banks prepared two wedges. When preparing a batch the quantity of dripping doesn't have to be multiplied; it will reflect the type of pan and the number of pieces being cooked in it.

Costing

14-course tasting menu, £85

The Black Swan doesn't work out food costs in the same way as conventional restaurants because many menu items are structured around raw materials produced on the farm. Whereas chefs might expect to pay £2 per kg of Crapaudine beetroot, the Black Swan is paying for the seeds and the labour on the farm.

Selecting and preparing the beetroot wedges Crapaudine beetroot has the size and tapered shape of a parsnip. Scrub off any dirt, then dry and peel the skin (1).

Each beetroot has to be large enough to form two wedges approximately 120g each, which look like slices of tart (2). Pare away enough trimmings to form the wedge and slice it in half. Each wedge should be 1.5 to 2cm thick. Complete uniformity isn't possible (3).

Slow cooking and smoking the wedges Put the beetroot wedges in a pan in which they fit comfortably, with enough melted beef dripping to come about halfway up the sides of the wedges (100g of dripping in a 24cm frying pan would be about right for two or four wedges) (4).

Over the gentlest heat allow them to cook like a confit, turning them at regular intervals. They will need to cook for about four hours. They are ready when the inside is soft and the outside has a thin sugary crust (5).

To smoke, put the wedges in a lidded container. Fill it with oak smoke from a smoke gun and keep sealed until ready to serve. When preparing a batch, fill a suitable tray, such as a Gastronorm, with the wedges in a single layer. Wrap them in clingfilm and make a small hole in the top. Put the smoke gun nozzle through it and fill it with smoke, then seal the hole with more film (6).

Juicing the trim and making the glaze Using a professional centrifuge juicer, extract the juice from 2kg of roughly chopped trimmings. They are about 87% water, so expect to obtain approximately 1.5 litres of juice (7)(8).

Pickling the discs Allow three red and three golden 2cm x 1.5mm beetroot discs per portion and scale up accordingly. Make a pickling liquor â" boil 50g sugar, 50ml white wine and 50ml white wine vinegar, or multiples of these quantities, and leave to cool.

Peel the beetroot, then slice on a Japanese mandolin â" do the golden ones first to avoid staining. Cut out discs with the smallest cutter (2cm) (9).

Put the discs into small vacuum pouches, keeping the two colours separate. Allow about 24 per pouch, with half the pickling liquor in each pouch. Seal on maximum pressure and leave at least an hour before use.

Smoked cod's roe emulsion

Serves 24

- 65g skinned and de-veined codâs roe

- 30ml water

- 15ml lemon juice

- 5g Dijon mustard

- 15g egg yolk

- Maldon salt to taste

- 125ml grapeseed oil

Put all the ingredients except the oil in a bowl or jug and blend with a stick blender until the mixture is smooth. Stream in the oil as for a mayonnaise, to obtain a stiff glossy emulsion. Fill a piping bag and chill until service (10).

Horseradish goat's curd

Serves 24

- 15g grated horseradish

- 100ml whipping cream

- 110g Innes goatâs curd

- Salt

Boil the horseradish with the cream. Cover and infuse overnight. Strain the cream through a fine chinois, using a ladle to extract as much of the liquid as possible. With a rubber spatula combine the cream and curd (donât beat it) and adjust the seasoning. Fill a piping bag and chill until service (11).

Linseed crackers

Serves 24-30

- 60g brown linseed

- 100ml boiling water

- Maldon salt

- Oil or oil spray

Put the linseed in a bowl and pour over the boiling water. Leave 20 minutes for the seed to absorb the liquid and swell, then season.

Spread on a lightly oiled silpat mat (12) and cover with film. Spread the linseed in an even layer by hand, then roll it out as finely as possible (13). Remove the film and bake for 30 minutes at 150°C in a conventional (non-fan-assisted) oven. The linseed is ready when it lifts easily off the sheet. Cool and break into small shards, then store in a sealed container (14).

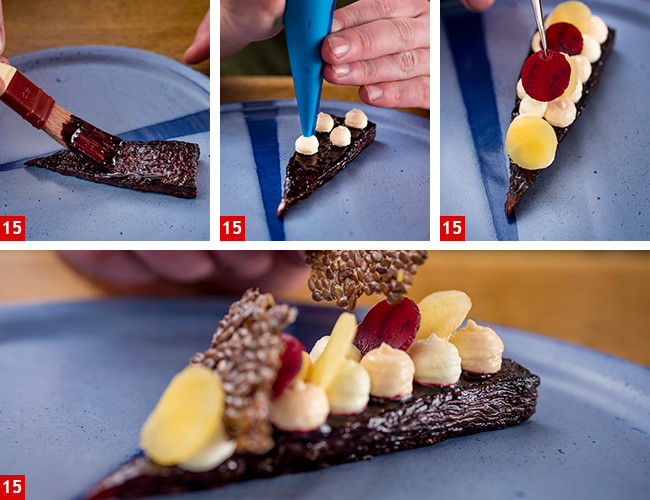

To assemble

Serves 1

- 1 wedge of slow-cooked Crapaudine beetroot

- 10g horseradish goatâs curd

- 10g smoked codâs roe emulsion

- 3 golden beet discs

- 3 red beet discs

- 3 shards linseed cracker

Ensure the beetroot wedge has been kept warm. If cold, the surface could have a congealed finish rather than a fine crust.

Put it on the plate and pipe six small dabs each of the curd and emulsion on it, covering the surface. Arrange the beetroot discs and shards between the curd and emulsion (15).

Three years ago, Banks and the rest of his family, which owns the Black Swan as part of an arable farming business, were hovering on the edge of insolvency. âWe were in the middle of nowhere cooking nice food but we were never, never busy,â he says.

That has changed dramatically. One obvious reason is his success on Great British Menu: âItâs brought us another hundred guests a week,â says Banks.The other has been a shift of emphasis: âWeâre farmers, we thought, so letâs go back to what we know. We have 2.5 acres by the Black Swan and another 2.5 down the road for growing the big crops and we decided that weâd cook what we grew ourselves. It was like starting over, and thatâs where my cooking is coming from. Now, thereâs a lot of originality. You wonât see the beet dish anywhere else,â he says.

The synergy has created unique culinary benefits, he insists: âOur sweetcorn season lasted for two weeks in August. When a guest came up to the restaurant a chef would run to the garden, pick an ear of corn, shave off the kernels, and toss them in brown butter and salt. Weâd serve a teaspoon of them in a brown bowl â" they tasted like biscuits,â he says.

âI donât feel the need to throw lots of techniques at a dish or make something fiddly or precise or perfectly round; itâs on my menu because itâs delicious.â

After changing his approach, Banks admitted that he had shied away from reading or watching TV in case he borrowed consciously or unconsciously from others. That phase has passed.

âI read, I watch TV shows and I eat out,â he says. The fact that he might pick up an idea here or there doesnât bother him. Itâs the DNA of the business â" farm plus restaurant â" that shapes his life and the way he treats his craft.