Masterclass: Chocolate with attitude by James Close and Maria Guseva

James Close, chef-partner of Raby Hunt in Summerhouse, County Durham, and his partner-chocolatière, Maria Guseva, share the secret behind a signature chocolate with Michael Raffael

First and last impressions count. To enter the Raby Hunt's dining room, guests step over a skull under a transparent glass sheet; another skull (duetting with a stone Buddha) watches them from an alcove throughout the meal. The last scene of the £110 tasting menu is a Belgian chocolate skull served with coffee.

The appearance and ganache filling inside the skull's shell isn't the same as it was less than a year ago. Then it was flavoured with rosemary, yuzu and honey. Now, echoing the Mexican Day of the Dead – where decorated sugar and chocolate skulls are a central part of the fiesta – it has a ground salted corn filling.

Even a specialist chocolatier with their own shop might think twice about the amount of labour going into the crafting of each batch. But if the end result creates the impact it's designed for, then the effort is worth it.

Planning

The first step is designing and ordering bespoke silicone chocolate moulds. These are available in the UK from Home Chocolate Factory (www.homechocolatefactory.com), Westfield (www.westfieldthermoform.com) and from Mol d'Art (www.moldart.be) in Belgium.

Guseva makes batches based on 12 sets of moulds, each one yielding 12 skulls (in two halves). This matches the weekly demand for the restaurant, which is open four nights a week.

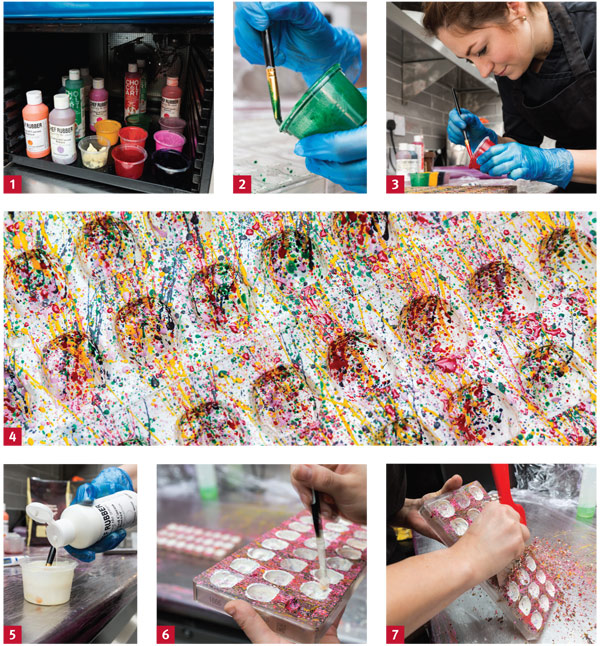

Step by step

- Make the lime gel 24 hours in advance

- Rub the moulds with alcohol

- Paint with coloured cocoa butters

- Paint with a layer of white chocolate

- Line with the couverture shell

- Make the chilli ganache

- Add the crushed salted maize to the ganache

- Fill the moulds with lime gel and ganache

- Set, unmould and solder together the front and back halves of the skulls.

Cost

The chocolate skulls, served with coffee, are the last course on the £110 tasting menu. They cost £2.50 each for customers who want to buy them as takeaway gifts.

Special ingredients

- Rubbing alcohol for the moulds

- Coloured cocoa butters (emerald, indigo, yellow, purple, red, pink and Moulin Rouge red)

- Alabaster white chocolate and white chocolate

- 63% couverture, 41% milk chocolate couverture (Alunga from Cacao Barry).

Special equipment

- A dehydrator cabinet can be used for melting the coloured cocoa butters

- Flat-tipped paintbrush, about 10mm wide.

Fluid lime gel

This can be scaled up as necessary. Allow about 5g per chocolate. Dissolve 3g pectin mixed with 17g caster sugar in 200ml fresh lime juice. Bring to the boil with 160g caster sugar. Boil and stir in 30g liquid glucose. Turn out onto a tray and cool until set. Blend to form a fluid gel in a VitaPrep or Thermomix. Fill a piping bag for piping into the chocolates.

Chocolate skulls

Note on quantities: Only some of the tempered couverture actually forms the shell, but the excess can be recovered and used again.

Makes 48 (4 sets of moulds)

- Cocoa butters: dark green, indigo, yellow, purple, red, pink, Moulin rouge red and neutral (about 15g each)

- 50g white chocolate pistoles

- 30g alabaster cocoa butter

- 600g 63% couverture pistoles

- 800g 41% Alunga milk chocolate

- 1 dried habanero chilli (more or less according to taste)

- 120g butter

- 160g dried salted corn nuts

Set the dehydrator to 34°C (the ideal melting point for cocoa butter) and put the coloured cocoa butters in it to melt (1). Add a pot of neutral cocoa butter, to be used for cleaning the paintbrush.

Cover the work surface with several sheets of film. Prepare the moulds by wiping each one with rubbing alcohol. This ensures that each chocolate will turn out cleanly.

Painting the moulds with cocoa butter is a Jackson Pollock process in miniature. Dip the brush tip into the melted green cocoa butter. Flick it over the moulds so that flecks of it go into each one (2).

Leave to dry. Clean the brush in neutral cocoa butter. Continue with the other colours (3). Each time, let the latest colour applied dry before adding the next.

When all the colours have set, the moulds will have a speckled appearance (4). Scrape the edges of the moulds.

Put the white chocolate pistoles in a bowl over a bain-marie and melt. Stir in the alabaster cocoa butter to obtain an ivory tinge (5). Paint over the other colours in the moulds to form a very fine layer and leave to dry (6). Scrape the edges of the moulds (7).

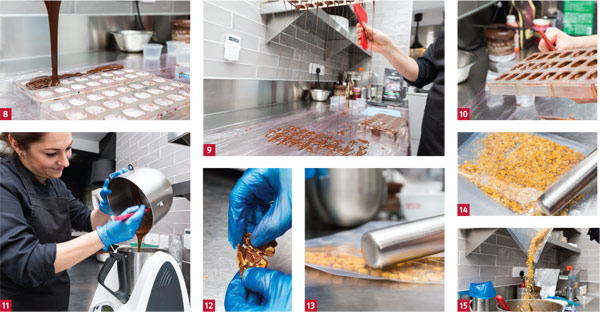

Temper the 63% couverture (when preparing the full batch, Guseva uses a ChocoVision tempering machine). Melt 450g of the couverture over a bain-marie and heat to 48°C. Add the remaining 150g of couverture and continue stirring until melted off the heat. During this process the temperature will drop. Reheat the tempered couverture to 31°C. At this point it will be viscous and on the point of setting.

Pour the couverture into the moulds to fill them (8). Leave for about 10 seconds. Turn them over to let the couverture drain out (9). Tap the moulds on the work surface. Scrape any left-over couverture off the top of the mould so that each skull section has a smooth edge (10).

Any couverture on the work surface can be recovered and used again.

Prepare the milk chocolate ganache. Melt the chocolate in a bain-marie and heat to 40°C. Transfer it to a Thermomix (11), add three-quarters of the chilli (12) and blend for three minutes. Taste the chocolate. If it needs more chilli (depth of flavour varies considerably from one to the next), add the other piece and blend three minutes more. Taste again. Add the butter and blend until it's emulsified.

Put the corn in a large vac pack bag (13) and grind it coarsely with a rolling pin (14). The ideal texture is akin to mignonette pepper. Stir the corn into the warm ganache** (15)** and fill a disposable piping bag. Leave till it sets to an easily pipeable texture, no higher than 26°C or it will melt the shells.

To fill the skull halves, nip the end of the piping bag containing the gel. Pipe a little (less than a coffee-spoon) in each one (16). Pipe the soft ganache into each skull half so it fills the cavity. Scrape the moulds' surface to obtain a smooth surface with no rough edges (17). Chill to set.

To finish the skulls, turn out the halves (18). Place the flat surface of an unmoulded chocolate (the front or back of the head) on a heated metal tray (19), long enough to melt the edge and fix it to a matching half so as to form the completed skull (20).

James Close and Maria Guseva

Maria Guseva has just added the finishing touches to the habanero-flavoured ganache in the Thermomix. James Close comes over and tastes it. "t could probably have done with a bit extra chilli," he says. She demurs, reminding him of past clients who have found the taste over-pungent.

The scene echoes the days when Albert Adrià developed recipes for brother Ferran at his laboratory in Barcelona. The great man was the inspiration behind an idea, and he had the final say, too, but it was the younger brother who beavered away until a recipe was perfect. The parallel won't stand too much scrutiny. The Raby Hunt isn't El Bulli in its prime; rather, it's a work in progress from a naturally gifted chef. "When we put a new dish on the menu," Close concedes, "It's probably about 70% of the way there. It needs about another three weeks before it's fully formed."

Past interviews with Close have stressed the self-taught background and his years as a golf pro. As a footnote they cover his experience pot-washing at Headlam Hall in Darlington or helping out at the small country house hotel his German mother ran. What they miss is a lifelong fascination for restaurant food. "I remember going to London when I was 10 and reading through a TGI Fridays menu from top to bottom."

One of the keys to his rapid ascent has been his willingness to absorb ideas from sampling other chefs' cooking, and networking with his peer group helps him acquire skills that he may apply when devising his own concepts. "All my ideas start with techniques or ingredients."

He doesn't take notes or draw sketches; instead, he visualises how a dish may look on a plate. Like an author, he knows where he wants to start and finish, but the chapters in between can be straightforward or sometimes a slog. According to Guseva, the development and the day-to-day running of the restaurant have changed since the extension and refurbishment of the kitchen. "When I started four and a half years ago, it was so hot I had to go outside to allow the chocolate cool down," she says. "James would sometimes lose it and shout. That doesn't happen now.

"The kitchen can't function without him. He never misses a service. The chef always being there is more common abroad than in Britain. If James wants or has to be away, we close."

Close recognises that his second Michelin star has been a game-changer, both for himself and the industry. From being the "only one star" in the North East, he has joined an elite of just 20 in the UK with two stars. Calling the Raby Hunt his addiction or obsession would, he believes, be an exaggeration. "You have, though, to give it 100% every moment you are there."