From racism to rebirth: UK’s Chinatowns on recovering from the pandemic

The tight-knit communities of the London, Birmingham and Manchester Chinatowns have been hit hard by the pandemic, their atmospheric shops and restaurants, a draw for crowds of tourists, being wiped out overnight. Georgina Quach looks at how operators are finding a pathway back to profit.

When restaurateur James Wong woke up one morning in March 2020, the future of Birmingham’s oldest Chinese restaurant was suddenly forced out of his hands.

Chung Ying (pictured above) was converted from a synagogue into a restaurant by Wong’s parents in 1981, and it kicked off the establishment of Birmingham’s Chinatown and Brummies’ love for Chinese food. For four decades, his eaterie has seen families, friends and strangers gathered around steaming towers of dim sum, but when government ministers triggered the ‘stay at home’ order, Wong found himself saddled with excess produce, sky-high bills and an anxious workforce – as well as a fear of catching the virus.

Birmingham’s historic neighbourhood, home to many Chinese-owned eateries, shops and karaoke bars, turned into a “ghost town,” says Wong, who is also chair of the Southside Business Improvement District (BID), which represents Chinatown.

“The bills were up to my eyeballs. Utilities, rent, suppliers and contracts all had to be paid, but there was no money coming in,” he says. By autumn, the Birmingham-born restaurateur had racked up six-figure debts. Office restrictions had crippled the steady lunch trade on which Chung Ying’s sister restaurant in Birmingham’s business district had depended and Wong had no option but to close the once-bustling venue for good.

“I was thinking ‘what is the point?’ You work so hard to open the restaurant and keep up momentum, then you are forced to close,” says Wong. The decision was not taken lightly, he explains, and the closure itself came at a huge cost.

But, even though shutting his latest venture had dented his pride, Wong was determined to keep the original Chung Ying restaurant open for takeaway throughout the pandemic.

“It was a pretty scary time [when the outbreak began] because while everyone was at home, locked away, we had to keep our business going. We were only managing to make 10% of what we would normally make.”

Running a takeaway was alien to Wong, who recalls the “bedlam” of their first weekend, when patrons had to wait over three hours for food as delivery drivers couldn’t cope with the demand. Although morale was low, Wong’s staff – many of whom have served Chung Ying for more than 10 years – were willing to weather the challenges.

“A lot of my peers have said it is impossible to get staff at the moment. Because I stayed open all the way through, a lot of the staff have been very loyal to us – I see them more often than I see my own family. I feel lucky that my guys have stayed.”

Because I stayed open all the way through, a lot of the staff have been very loyal to us

A community on edge

Terry Lim, who runs Yuet Ben restaurant in Liverpool’s Chinatown with his wife Theresa, say customer levels are down by 75% because his predominantly middle-aged customers are still scared of catching coronavirus.

“I am struggling to stay sane and not be depressed,” says Lim. Yuet Ben – one of Liverpool’s oldest Chinese eateries – has welcomed famous faces including Cliff Richard and Dawn French during its 50-year history. “Fortunately, we own the building and received support from our local council, in the form of a business rates rebate and financial grants,” he adds.

Chinatown’s mix of mainly independent food retailers and restaurants was a source of strength before the pandemic started, drawing vast crowds even as the UK high street suffered. That’s now become its greatest weakness during the pandemic as tourist numbers have fallen, leaving the many small operators that run Chinatown’s noodle bars and boutiques on the edge of a precipice.

In London, vacancy rates in Chinatown have more than doubled during the pandemic, with shops and restaurants cutting leases they cannot afford. The number of empty units in Chinatown and Soho landlord Shaftesbury’s estate has more than tripled since the outbreak began, according to Bloomberg.

“Our landlord has been very efficient and supportive in helping us run as normal as possible, but lockdown and restrictions are very, very difficult to manage for everyone in the sector,” says Tony Fang, founder of Bubblewrap, a waffle shop based in London’s Chinatown.

The purveyor of the lavish Hong Kong street snack – a Generation Z hit, amassing 33 million Facebook video views – is currently running at 45% of its normal volume. “Last year was a lot worse and we were constantly feeling anxious about the changing regulations,” says Fang.

Many Chinatown workers had hoped this phase was over. But it was not to be. Despite Britain having one of the world’s fastest vaccination programmes, businesses that were gearing up for 21 June must now wait another month for their ‘freedom day’.

“Government policy and never-ending restrictions have decimated hospitality,” explains Julia Robinson, manager of Birmingham’s Southside BID. She claims the state needs to do more to stem firms’ cash flow, as Covid limits continue but financial support winds down.

“I know for a fact that [the delay] will push some over the edge. Some have only been hanging on for 21 June. Many businesses are now scrambling to find £30,000 to stay closed for another month,” she says.

Eight of the 88 businesses she oversees have been closed for the 17 months since the outbreak, while many of those that did return in spring are running at 10%-20% capacity. In particular, the delay to easing restrictions has stifled Chinatown’s opportunities to host big parties during Chinese wedding season, which would normally be a huge boost to bookings.

The news has been especially devastating for those who invested so much into putting every possible safety measure in place. “It’s like climbing over a wall to then find a bigger wall,” says Wong, who spent almost £25,000 on dividers, an outdoor seating area and other protections to help reopen his premises safely.

“We’re doing all the right things, but no one seems to care, and we certainly haven’t been rewarded for doing so,” adds Robinson.

Her priority now is to protect Birmingham’s beloved cultural hub from permanently disappearing. Robinson stresses that the government’s perceived neglect of hospitality during the crisis – worsened by stop-start restrictions – could turn much-needed, fresh talent away from an already battered industry.

“We now have massive debt burdens and a recruitment crisis because no one wants to work in the sector any more. Who would want to bet their mortgage on opening a new restaurant now?”

We now have massive debt burdens and a huge recruitment crisis because no one wants to work in the sector any more

She also highlights the lack of skills programmes focused on training the top chefs of the future. “Not just in my city, but all around the country, no one has got hospitality in its sights as somewhere to invest in.

“The whole industry feels completely abandoned. We’re lobbying really hard to try to get some support at the very least to the ones that never managed to open their doors,” says Robinson, the frustration evident in her voice. Following the June announcement, her WhatsApp chats with hospitality businesses were flooded with angry outcries – demanding both mental health support and a militant pushback from those business owners who were being hurt the most.

“There are issues with mental health and substance abuse in the hospitality industry, but often people are too busy or distracted to deal with it. I’ll talk to managers and they’ll say ‘I’m fine’ even though, when you drill down, you find they’re not.”

Bouncing back

Chinatown’s tale of extreme hardship is also a tale of resilience. In the midst of all these challenges, small business owners evolved. When the state ordered tighter restrictions on seating, many Chinatown eateries moved their tables outdoors. Jeremy Mun, manager of Malaysian Delight restaurant in Birmingham, says Southside BID helped his restaurant adapt to alfresco dining by sourcing tables and chairs.

“Pedestrianising Chinatown London has been a massive success and really opened the authorities’ eyes as to how we can bring life to traditional ‘transit’ areas,” explains Carl Kjellqvist, managing director of Korean fried chicken joint Wing Wing. “The numbers of Londoners braving the rain and cold to eat outside was heartening to see,” he adds.

As streets emptied of diners, Chinatown’s community stepped up to fill the void, spreading generosity in creative ways. In Birmingham, Chung Ying donated thousands of meals to NHS workers and hungry children. When Chinatown hosted a vaccination clinic, local businesses brought out chairs, water and food to queuers. Wong says in a decade the crisis will simply be a blip in the timeline.

“It will be a part of history,” he says. “Closing one of my restaurants was the end of a dream, yes, but every person has ups and downs. At least I have my good health, house and family, which is the most important thing,” he adds, reflecting on all the added time he gained during the pandemic to spend with his two young children.

Growth has been another hidden benefit of lockdown, in that the ban on indoor dining propelled many small businesses into the digital era. Julia Wilkinson, director of restaurants at Shaftesbury, says: “During the period of full lockdown, Chinatown London successfully became a virtual village, maintaining engagement between consumers and operators via a diverse range of social media platforms. It then evolved to become a takeaway hub, with over 30 operators providing food-to-go and delivery from June last year.”

Lim used Yuet Ben’s Facebook and Instagram to both update their loyal restaurant-goers and attract newcomers. Mun found Malaysian Delight’s business has surged by 40%, having generated a new group of regular customers during lockdown. But the new challenge, he says, is sourcing ingredients, which has been disrupted by Brexit and shipping delays: “Some ingredients are now being flown to Europe, rather than transported by sea, so the price has doubled.”

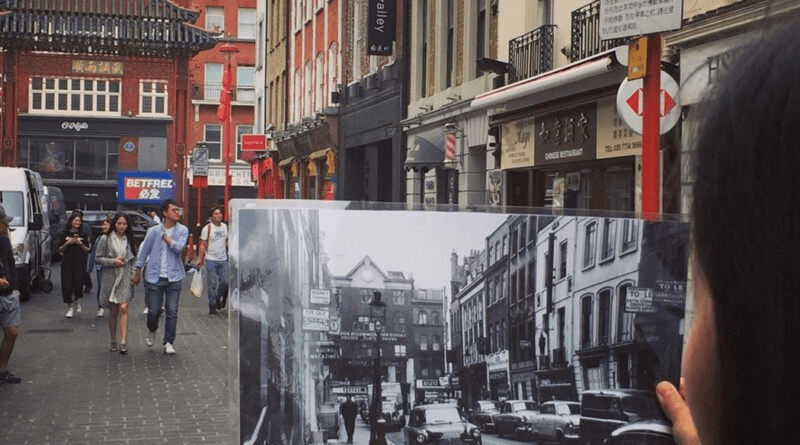

While Chinatown prepares itself for an uncertain future, educational projects like China Exchange are also preserving and sharing the community’s quirky and rich past.

Freya Aitken-Turff, chief executive of China Exchange UK, says the charity is documenting the undocumented food cultural heritage of London’s Chinatown. “Volunteers will develop a food heritage trail around the area to show how, for example, the first shop to import pak choi to the UK changed the culinary landscape,” she explains.

For many businesses, recovery means getting back to doing what they do best. As China- towns across the UK regain their footing once again, Wong says he is sleeping easier – disturbed only by his restless young children, rather than mounting bills.

“I personally can’t wait to have a good old night out with friends and for things to go back to normal,” he laughs.

Safer but still scared

“East and Southeast Asian people, like international students, are more reluctant to return,” says Aitken-Turff. She says Asian community support services have been busier than ever.

Jeremy Mun, manager of Malaysian Delight restaurant in Birmingham, says his business is recovering but still slow, since a fifth of his customers are international students. Many are from China looking for a taste of home. During Covid, Mun’s staff were too scared to return.

“There were only a few of us working. Luckily, the government furlough scheme helped us to cut down our expenses,” he says.

Yuet Ben’s Terry Lim adds: “We are fortunate that Liverpool is a very tolerant and strongly anti-racist city. Of course, we are aware of the racial challenges elsewhere in the UK.”

We are fortunate that Liverpool is a very tolerant and strongly anti-racist city

For some, it is precisely this solidarity in the fight against anti-Asian hate which will enable Chinatown to bounce back.

“It has been heart-wrenching to see a rise in discrimination against Asian people,” says Carl Kjellqvist of Wing Wing. “I have every faith that this difficult period will only make people more determined to stand up and help lead the post-pandemic recovery.”

Dispelling distrust of Chinatown

In many ways, Chinatown has suffered for longer than most hospitality businesses in the country. Months before the first lockdown was announced, reports of a virus outbreak in China curbed footfall across all UK Chinatowns. President Trump called the disease “the Chinese virus”, and hate crimes explicitly targeting Asians have tripled since the start of the pandemic.

Bonnie Yeung, managing director of the longstanding Yang Sing in Manchester’s Chinatown, says: “In the early days of Covid-19, the council produced posters with messages such as: ‘Have you been to China? Have you come from Wuhan?’, which simply did not help to protect our community from the maelstrom that was swirling around our neighbourhood.

“There was not a single business that didn’t see a downturn in visitor numbers during that period. It was sad.”

Bonnie speaks of Chinatown as “home,” where people of all walks of life gather and feed under its cosy canopy of steamy air and the smell of hot chilli oil.

“Hospitality is about feeling pleasure, well looked after and safe. It can’t be reduced to just serving food. Our local policing team have been brilliant and set up coffee mornings and events to educate our community, particularly for vulnerable members like our elders. I feel very protective over my community and would not hesitate in challenging prejudices.”