Masterclass: roast hare

At the Freemasons at Wiswell in Lancashire, Steven Smith has moved away from the one-pot approach of the classic hare recipe to create a delicate and flavourful dish.

Skinned and paunched, full-grown brown hares tip the scales at two to three kilos. Subtract the head, carcass and extremities, and there's less meat on them than on a chicken. The two loins that make up the saddle add up to a decent-sized steak.

Old English cookery books recommended hanging a hare for a long time before cooking. The time-honoured jugged hare dish is a stew simmered until the meat falls off the bones, and lièvre à la royale, one of the most honoured recipes of haute cuisine, has meat tender enough to eat with a spoon.

Both of these classics start from the premise that the cook puts the entire chopped-up beast into the pot. Simmering it wholesale makes no distinction between the separate joints, which fails to do justice to the tender loins, which have a unique taste and texture. Their typically gamey meat is more delicate than, say, roe deer and, in the mouth, more tender.

Across the British Isles, different rules cover the open season for hunting hare: in England and Wales, they can be hunted all year round; in Scotland, only between 1 October and 31 January; and in Northern Ireland, from 12 August to 31 January. They aren't endangered but are much less common than rabbits.

Hanging both furred and feathered game went out of fashion decades ago. At the

Freemasons at Wiswell in Clitheroe, Lancashire, currently the AA's Restaurant of the Year (England), Steven Smith buys freshly killed hare weekly and processes it without any further maturing.

He doesn't build his recipes around strongly flavoured game stocks that risk overpowering the dish; instead, to accompany the saddle, he has developed a grand huntsman sauce without any bones or trimmings. He wants to focus the diner's attention on the meat.

Smith obtains only one generous à la carte portion from a hare, but the haunches figure on his lunch menu and the forelegs are used in pre-lunch or dinner snacks.

Planning

The Freemasons at Wiswell closes Mondays and Tuesdays, when the chefs do the hare butchery and basic prep for the week ahead as well as making the grand huntsman sauce. A typical batch size would be 20 hares. The accompaniments (parsnip and apple purée) slot into the routine mise en place.

During service, each portion of loin is ‘roasted' on the plancha, smoked in front

of the customer and then plated. The hare tartare is mixed to order.

Costing

As an owner-chef, Smith says he doesnât answer to a managerâs budget. He prefers to have a gross profit in the mid-60s, which means he can serve more customers and guarantee the consistency of each portion.

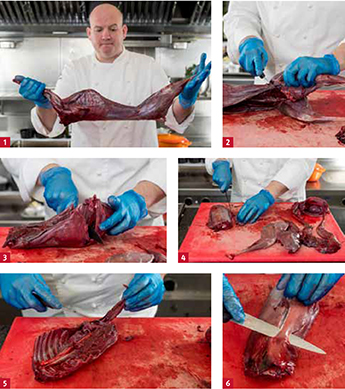

Hare saddle preparation

Cut across the backbone at the point where two ribs attach to it. This leaves the untrimmed saddle intact (3).

Turn it so the loins lie on the board and remove the fillets either side of the backbone. Reserve for the tartare. Trim the belly-flaps, cutting through the ends of the rib-bones (4).

Turn the saddle over so the loins are on top. Using a sharp filleting knife, pare away the silverskin âstockingâ over the two eye muscles (5-6). You will have a saddle with four to five ribs either side of the backbone.

Grand huntsman sauce

Although the name has ties to the classic French sauce grand veneur, this is very much a modern reworking of it. To make the dark-brown chicken sauce base, we put 20kg of roasted chicken wings and 10 large onions (skin-on) into 40 litres of water. Boil, skim and simmer for three hours, then strain. Add 250ml tamari (which is thicker and less salty than soy sauce and gluten-free) and 250ml sherry vinegar and reduce to about five litres. To make 300ml (six portions), use the following quantities:

- 120ml Côtes du Rhône-style red wine plus 1tbs

- 300ml chicken sauce base

- 3tsp smoke powder [from MSK Ingredients]

- 20g redcurrant jelly

- Sherry vinegar and red wine to finish

Reduce 120ml red wine to a syrup. Add the chicken sauce base and bring to the boil. Stir in the smoke powder and then whisk in the redcurrant jelly to dissolve it. Add the rest of the wine, but donât cook it out. Taste the sauce and adjust with a few drops of sherry vinegar and/or wine to finish.

Transfer to a squeezy bottle and keep hot at 65°C in a bain marie throughout service.

Wild roast hare loin smoked over Wiswell Moor pine with grand huntsman sauce

Note: the smoked saddle is presented at the table before it is carved and plated in the kitchen.

Serves 1

For the tartare

- 40g hare fillet, hand-diced

- 1tsp each chives, capers, gherkins and shallots

- 1 drop Tabasco

- 3 drops Worcester sauce

- 1 heaped tsp Granny Smith purée (see box)

For the hare

- Rapeseed oil

- 1 saddle hare

- 1 segment of parsnip, halved (see box)

- 1tsp honey

- 2 large handfuls of fresh pine needles

- 4 apple slices (use a Japanese mandolin)

- 30g parsnip purée (see box)

- 30g apple purée (see box)

- About 10g Stilton, crumbled

- Pine salt

- 50ml grand huntsman sauce

- Chocolate, grated

Mix the tartare ingredients together and form into a round patty.

Heat the oil on the preheated plancha. Unwrap the saddle from its vac-pack. Pat it dry and sear on the plancha, meat-side down. When itâs well-coloured, turn and continue cooking. Itâs ready when the surface of the meat feels like a rare steak. Remove from the plancha and rest.

Put a thick layer of pine needle sprigs in a Le Creuset-style pan and lay the saddle on top. Fire the leaves with a blowtorch. Cover the pan and leave to smoke for about two minutes.

Take the loins off the bone and trim neatly.

To assemble, put the tartare on the plate and cover with a slice of apple. Spoon small piles of hot parsnip purée onto the plate, interspersed with apple purée. Lay the sliced loin on top of the purée, and then lay the parsnip segments on top. Finish with extra apple slices, the crumbled Stilton, the grand huntsman sauce and the grated chocolate.

Roast and puréed parsnip

Use medium-sized scrubbed parsnips with tender cores. Carve them into spike shapes and cut these in half. Vac-pack them four pieces at a time with 10g each

of butter and duck fat. Poach for 70 minutes at 85°C. Chill ahead of service.

Granny Smith purée

Boil a kilo of quartered, skin-on Granny Smith apples with a litre of apple juice until very tender. Blend the apples and then add 1g of agar agar per 100g of the mixture. Chill the purée. Incorporate one to two teaspoons of xanthan gum. Blend again and transfer to squeezy bottles. The purée should hold its shape when squeezed onto a plate.

Steven Smith

Steven Smith isnât ashamed of his ambition to own the best pub around. Lots of pubs, he argues, serve awesome food, but somewhere along the line they turn into restaurants. He wants to cook to the best of his ability, but wonât let the Freemasons at Wiswell lose its identity as a local.

to be, a challenge for him. âOur secret is that we make it a place for everybody,â

he says. âWe have many of the elements of a high-end restaurant, but we havenât lost touch with our community. Last night, we had 20 or 30 locals come in. I have six or seven gentlemen in the village who come in every Thursday evening. They have chips and mayonnaise at the bar and five pints apiece â" and theyâre happy.

âOur motto is to take the food seriously, but not ourselves. My parents ran working menâs clubs, so the pub side sits very comfortably with me. But it also helps me to do what I want with the food.â

Smith admits that he never did the rounds of big-name chefs when he was learning his craft: âI worked under very excellent chefs who did have that background. I was in small kitchens where you have to do lots of things,

so you progress that much quicker.â

After eight years at the Freemasons, he believes he has developed his own style. Smith has devised an in-house system that can cope with, say, a Champagne party for 20, while a couple in the bar is eating bowls of soup. Lobster, hand-dived scallops and turbot on the à la carte during the week devolve into seafood gratin for Sunday lunch, when heâll serve 120 covers.

âYou could come here five days in a row and eat superbly, but each day would be a different occasion. On Wednesday it might be the early-evening menu [£25 for three courses]. On Thursday it might be an event, such as a wine club tasting. On Friday you could pop in for steak and chips for your tea. On Saturday you could push the boat out, and on Sunday have roast beef for lunch.â

This versatility is born of the survival skills heâs acquired by operating in a location thatâs out of the way. Having had to graft has also, Smith believes, made the food better. The consensus among the critics and the guides is that heâs right.