Masterclass: hake steak in green sauce by Elena Arzak

Elena Arzak's take on the Basque classic of hake steak in green sauce with clams is a celebration of simplicity. Michael Raffael reports

The hake dish does, though, reflect the regionâs cookery at its best. Before the birth of New Basque Cuisine more than 30 years ago, San Sebastián had more than 100 gastronomic clubs, where groups of friends cooked for each other.

Today, there are just as many. The in-depth appreciation of good ingredients and good cooking that is central to Basque culture explains why the city has become as influential in its way as Lyon was when provincial French cuisine ruled.

According to Elena, developing a palate is a basic skill for any chef. She says that before venturing into the complex jungle of the modern professional kitchen, every chef should learn how to taste.

Cost

The price for large, line-caught hake varies between £7 and £12 per kilo, depending on availability. Filleted and prepared as a pavé, a 4kg fish will yield eight 150g portions, with plenty of trim for stocks, fish soups, etc. At the Ametsa with Arzak Instruction restaurant at the Halkin hotel in Londonâs Belgravia, hake main courses sell for £29.

Merluza en salsa verde con almejas (hake in green sauce with clams)

Serves 1

40ml soft-flavoured Spanish extra virgin olive oil

1tsp chopped garlic

1tbs (approx) chopped broad-leaf parsley

1tsp plain flour

Water

10 clams or cockles

Salt

150g pavé of hake (skin on), about 3cm thick

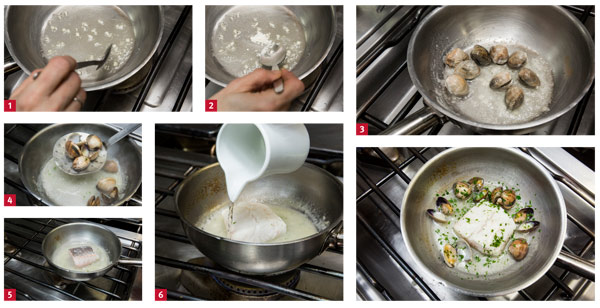

Heat the oil in a small (17-18cm) frying pan. It should be hot, but not smoking. Add the garlic with just a pinch of parsley, and let it sweat without frying (1).

Stir in the flour and cook it out for a minute or so without colouring or burning (2). Add a splash of water (about two tablespoons) and stir until the sauce base forms a liaison.

Add the clams and cook them until they open â" roughly three minutes (3). Itâs a good idea to speed the process by covering the pan with a lid. If any donât open fully, prise them open with a knife point. Take the clams out of the pan and let them sweat out their juices on a plate while you are cooking the hake (4).

Salt the hake lightly, because the clams are already salty, and place it flesh-side down in the pan over a medium flame (5). Add a little extra water and let it cook gently without boiling.

Turn over the fish after three minutes, and cook for another one to two minutes (6).

Turn the fish again, so the white flesh is uppermost. Add the clams back in with any rendered liquid (7). Stir in the parsley and baste with the sauce, which should have a light coating consistency. Adjust it if necessary.

Take the pan off the heat and rest the fish for three minutes on a rack above the range. Flash the fish under the salamander for a few seconds before serving.

Note: some Basque restaurants use fish stock rather than water, but this gives a less delicate, clean taste.

Txakoli

Made from white Hondarrabi grapes, Txakoli is the quintessential quaffing wine to accompany Basque seafood dishes.

It has three separate PDO (protected designation of origin) growing areas: coastal Getaria, Bizkaia and inland Arabako (produced around Ãlava on the fringes of the Rioja region).

In the pintxos and tapas bars, there are two styles of âhigh pouringâ. Either the bottle top is held to the rim of the glass and the bartenderâs arm is raised until itâs above head height; or a waterfall effect is created by holding the bottle high and the glass low.

Either way, the aim is to create a flow of wine while releasing the residual carbon dioxide. In sit-down restaurants, the best Txakolis are already spritzy and can be poured directly from bottle to glass.

Elena ArzakÂ

Elena Arzak says she has never suffered the humiliations of gender inequality. âI was brought up in an atmosphere where nobody bothered whether I was a man or a woman. The only thing that mattered was my ability to do the job.â

Read the potted biographies of her professional career and youâll learn she took over the âtres estrellasâ of the restaurant in San Sebastián from her father, Juan Mari Arzak. But thatâs a limited view of the father-daughter relationship. For a start, he inherited the family restaurant from his mother, who was the third of six generations to have run it. Basques, Elena points out, have a strongly matriarchal society, and women are often the decision-makers.

Her relationship with her father remains as strong as it always has been: âIâve been working with him for 25 years [sheâs 48], and as long as heâs alive, heâll always be my chef, even if he comes into work only a few minutes a day.â

Together with Pedro Subijana, his San Sebastián compatriot at three-Michelin-starred restaurant Akelarrre, Juan Mari created the Nueva Cocina Vasca [New Basque Cookery] movement more than three decades ago. That era ran its course, but it has left a unique footprint with a string of world-famous restaurants â" such as Mugaritz, Azurmendi and Berasategui â" dotted about the region. In San Sebastián and Bilbao, bars serving pintxos (aka tapas) set the standard for Spain and the rest of the world.

Elena also pays tribute to the way her father helped change the Spanish attitude to dining out: âHe made it possible for everybody to go to a restaurant. It stopped being a class experience reserved for the cultural or moneyed elite.â

Elena speaks five languages fluently and she carries some classy stamps on her culinary passport: Pierre Troisgros, Alain Ducasse, Michel Bras, Albert Roux and Ferran Adrià . Her back story has equipped her for running a world-famous restaurant. Itâs something she does in her own way.

For starters, 80% of her staff are women, not because of any political agenda, but based on merit and compatibility. Despite all the technical and technological changes to the kitchen, no dish ever goes on her menu unless it tastes right.

âItâs what comes first,â she says. âAnything that doesnât deliver isnât worth doing. Yes, of course, we look at things like freeze-drying or distillation, but they are a means to an end. At Arzak, we are focused on getting the balance between flavour and originality.â

She adds: âSome people never develop a sense of taste.â She defines this as identifying roundness, when an ingredient, stock or finished dish tastes exactly as it should in its purest form.

That doesnât mean everybody has to have the same palate. âMy father and I have different views on sweetness,â she says. âHe belongs to a generation when the taste of sugar was much more up front. Iâve persuaded him to adjust to less sugary desserts, but the change has been difficult for him.â

A-list restaurants canât stand still. Every year they have to reinvent their menu in the same way haute couture designers do. Elena relishes the pressure to create. âYou canât repeat the past, you canât go back,â she says. âWith my father, Iâve looked at dishes we were doing 20 years ago and I think: âOh dear, how dated they look.â What we want to do is identify values that last without blocking innovation.â

Anything, she admits, can trigger a fresh idea. While waiting to catch a local bus in San Sebastián, she noticed a poster with a frog on it. A second bus came along: same thing. âI contacted a friend at City Hall, who told me a local frog species saved from extinction had been made San Sebastiánâs emblem. So now when customers dine, I serve them moulded frog bonbons on a crystal platter that looks like water.

âThereâs so much information available in the media and online from all over the world that could serve as an inspiration, but I want those who come to Arzak to know where they are.â

The reference to her home townâs public transport carries the coded message that Arzak is part of its community. She says: âWe have a family restaurant. It belongs to me, but we arenât millionaires. Weâre comfortable; we donât need money, but weâre happy as we are.â

Staying close to her roots has been a conscious decision. Elena has spurned opportunities to turn herself into an international brand like other three-staristas. She doesnât, she says, criticise the Robuchon, Ducasse or Ramsay approach: âThere are chefs that can direct, manage and devolve.â Left unsaid is the implication that she may not be one of them.

She has, though, one outpost: the Ametsa with Arzak Instruction restaurant in the Como-owned Halkin hotel, London. She accepted the offer because she liked Comoâs owner, Christina Ong. âWhen my dad and I were approached, we decided we couldnât take it on all by ourselves, so we set up a company with three chefs working in our R&D laboratory in San Sebastián. One of them visits on a regular basis because I canât come every month.â

The success of what is something of a testbed means that she hasnât shut the door on future ties â" so long as they donât affect her home base. Itâs possible, Elena insists, to be a luxury, global destination without losing touch with her own constituency.

âWhen I was little, there was already an international clientele in San Sebastián. The Guggenheimâs opening in Bilbao brought more. At the same time, Basques would save up their money and come to Arzak for special occasions. Everyone received the same welcome and that hasnât changed.â

The bottom line is that she likes hospitality: âCooking, treating people well â" I donât mind whether he or sheâs from Jamaica or Singapore.â