History in the making: How Clare Smyth is giving her brigade a lesson in the classics at Core

For Clare Smyth, chef-patron at Core, looking back can enhance the future. Chris Gamm spoke to her and her protégés about how consulting the past is firing up their passion

The godfathers of haute cuisine are a narrative that runs through the career of Clare Smyth and the plates â" and shelves â" of her first solo restaurant, Core, in Londonâs Notting Hill.

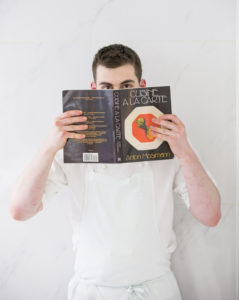

It was Anton Mosimannâs Cuisine à la Carte, with its striking, retro, tomato soup on the cover, that lit the spark in the 15-year-old Smyth, and the book takes pride of place on the shelves at Core today.

âAs a kid from Northern Ireland, the story of Mosimann, a chef at the Dorchester, seemed so glamorous. That inspired me to move to England, to go to college and become a chef. I read all of the basics in Cuisine à la Carte, all the mother sauces, then tried to replicate them.â

Her thirst for knowledge then led her to the Roux brothers, Paul Bocuse and Auguste Escoffierâs Guide Culinaire (âtwice, cover to coverâ), where she developed an understanding of the techniques underpinning classical cuisine.

âThe more I learned as a youngster, the more tools I had in my box to pull out,â she says. âSometimes now Iâll do a very classical dish in quite a contemporary way, and all the guys will be like, âwow, thatâs awesomeâ. And Iâll say, âI got it from Escoffier or Paul Bocuse, these books we have here at the restaurantâ. Itâs so cool when you can pull out a recipe and it inspires everyone because itâs great cooking.â

The books of the masters may have taught Smyth the techniques of haute cuisine, but it was during her time in the three-star kitchens of Gordon Ramsayâs flagship Chelsea restaurant and Alain Ducasse at Le Louis XV in Monaco that she mastered them.

âI really loved being in a three-Michelin-starred environment for 15 years of my life,â she says. âI just loved working at that level. Gordonâs management style was very strong and he was a real technician. That precision is something I love.

âWith Alain Ducasse, thatâs very much where the respect for being a chef, for produce, cooking and the history of cooking, came from. We learned the basics of classical French cuisine, of how to cook properly. Everything would be made with pestle and mortar, chopped by hand, turned à la minute and cooked à la minute in service.â

A favourite saying in the Core kitchen comes from Winston Churchill: âThe farther backward you can look, the farther forward you will see.â For Smyth, itâs her knowledge of classic techniques and the chefs that have come before her that allow her to innovate and evolve her cooking today.

âIf you are Roger Federer, once youâve mastered all the techniques in tennis, then you start to understand the matrix, create your own serve and your own style. I think itâs really important to have that great foundation to build upon,â she says.

However, knowledge of the basics is something that Smyth thinks is lacking in the young cooks coming through her kitchen in recent years. âThey donât know where they come from. They donât know the origins in the profession. They donât know why they wear those jackets or where the chef hat was created. Once they do, it gives them a better sense of pride in their profession.

âItâs very thin when you can do one dish or one thing, but donât know where it comes from. Thatâs really important for me: a sense of place, culture, history, knowing why you cook the way you cook. Itâs got to come from you, and not just from a picture. Iâm really proud of the history of being a chef, and I think itâs really nice to share that knowledge with others. It gives them that same passion.â

Back to school

Sharing her knowledge with the team is something that dates back to Smythâs time at Restaurant Gordon Ramsay, where chefs were invited to borrow books from the kitchen library. At Christmas, everyone was given a book linked to their section. This ethos, and the time for training that comes from running just eight services a week at Core, have allowed her to take team development to the next level.

âIf you want to be really good, youâve got to train every single day,â she says. âFront of house do knowledge sessions every briefing, and thereâs also a wider project that happens on a monthly basis. At the minute itâs wine month, and once a week one of the sommeliers does a talk on the basics for everyone.â

But the real schooling for her young kitchen brigade comes in the form of a weekly project, where one cook will research a great chef, classical dish or ingredient. If itâs a dish, theyâll learn all about that dish, cook it for a staff meal and tell everyone about its history. If itâs a chef, theyâll find out everything about them and present back to the rest of the team.

âWhen we lost Paul Bocuse, we pulled all the team together and told them heâd passed away and asked if everyone here knew of him,â says Smyth. âLois, whoâs 19 and had just started working with us, said she didnât, so that became her project for the week. She did a presentation and told a couple of funny stories about his character. Afterwards, I asked if she felt richer as a chef, now that she knew. She said she loved it. You can cook something, but to know where it comes from gives you so much more pleasure.â

The projects have also helped Coreâs international team learn about each otherâs cultures, traditions and history. âAlex is a Spanish chef and his family produce their own charcuterie. They sent some over and he did a presentation on it, which then inspired others to chip in. Tiago, whoâs front of house, said âin Portugal, we do it like thisâ, and Antonio, whoâs Italian, said âwe do it like thatâ. And suddenly youâve got a discussion about killing a pig, how they eat its liver fresh, how the older generations do it. And they share all the knowledge and stories of their culture and where theyâre from. It helps with team bonding and theyâre learning about tasting the produce. It adds a great richness.â

Itâs working, too, and the team speak with a passion for Bocuse, Mosimann and the masters to match that of Smyth herself.

âIâm very committed to this industry and Iâve got another good 20 years in me. Itâs up to people like me to put that knowledge back in and not just complain about skills not being there. Weâve got to try and do something about it, because I want to be in hospitality for a long time and these kids are going to have to come through and take it up.â

Going it alone

âOpening a restaurant is difficult, especially when I came from such a well-established, seamless place such as Restaurant Gordon Ramsay. Itâs hard when you start up and youâre standing at the pass with a brand new team, thinking âguys, this just isnât good enoughâ.â

Despite holding the enviable record of being the first female chef to hold three Michelin stars, receiving a perfect score in the 2015 Good Food Guide and being awarded an MBE for services to the hospitality industry, Smythâs first thoughts on opening her own restaurant in August 2017 were getting guests through the door.

âI didnât know how it was going to be when we opened, so weâre really grateful for the fact that people came. The business is quite strong, but that is something weâve got to make sure we keep working on,â she says.

Hitting targets allows Smyth to make improvements, including changing the banquettes, updating the lighting and putting in more acoustic panelling. âItâs about fine- tuning the vision and changing things that arenât quite right. You donât know when you move into a building how itâs going to work until youâre in it. Iâve got lots of ideas and vision for the place. It will take years to do, because some are quite expensive and Iâm not a billionaire. I didnât have a big budget; it was me going to the bank. But this is a real, sustainable business, economically and environmentally. It has to work. This isnât a vanity project, so it wonât be done in five minutes, it will take years.â

Despite the references to the past, her vision for Core is modern fine dining and attracting young people, both diners and staff, who have been put off by the formality of haute cuisine.

âWe donât want it to feel like a temple to gastronomy, but what we do in terms of food and service is at a very top level. But everyone should feel comfortable. I know how I feel as a guest and I want that to come through to our guests. Itâs about taking all the stuff away from fine dining that makes people feel uncomfortable: not knowing how to pronounce things on the menu or when the environment is a bit quiet and stiff.â

To achieve this, she took down the barriers between the kitchen and dining room and encouraged the chefs to interact with the diners. âThe cooks come out and serve a dish to every table. It is about getting them to connect with the guest, take responsibility and come out of their shell. They tell guests about the dish, where itâs come from, why weâve cooked it and how weâve cooked it.

âWhen we knocked down the wall, it was so we didnât have any barriers between the kitchen and dining room. The chefsâ connection with guests and front of house is a lot stronger, because we can see whatâs happening in the room, we can hear it, say hi to the guests and say goodbye.â

Despite having an eye very firmly on the present and hitting the business goals that allow her to fulfil her vision for Core, itâs the development of the next generation of chefs for which Smyth wants to be remembered.

âIn 20 yearsâ time, I hope the team have a greater knowledge and understanding of their profession. And I hope to have given them that foundation to enjoy cooking more and to have the ability and confidence to cook freely because they know why theyâve created what they have.

âWe want to love what we do. Itâs our lives, weâre here all day, every day, so we want to enjoy it. Knowledge gives you that passion. Itâs a really powerful tool.â

Ben Watson, senior chef de partie Project: mother sauces

âI told the team about these weird combinations that sound strange to us 100 years later. Recently, we were researching a peppercorn sauce and looked in Larousse Gastronomique to see the difference between how they made it back then and today. Itâs similar, but the original recipe had ham in the base, which Iâve never heard of. We put Alsace bacon in our version and it gave it a really nice, deep, smoky flavour. Maybe smoked pork belly was used, but you can see what was being done back then and what could really work with the sauce.â

Ross Bowles, chef de partie Project: Anton Mosimann

âIâve done four projects, but I really liked Anton Mosimann, because he is someone I felt I should have known about but never did.

âHis life has been inspiring. My favourite part of the story was reading about the opportunities he turned down in the early parts of his career. He got some chances that anyone would have loved to have and didnât take them, because he felt he needed to develop more as a chef. Even with really successful, incredible chefs, you donât often hear of them turning down opportunities because they need to go back and develop their skills.â

Lois Picken, commis chef Project: Paul Bocuse

âI found out he was born in the same house he died in. He got his first Michelin star in 1958, his second in 1962 and a third in 1964, which shows how much dedication he had. He waited all those years for them.

âYou see some elements in what we are creating. Iâm new to this industry and I didnât know how much I would connect to the old school, but I see a lot of it here. Itâs rooted in Bocuse and Escoffier, who are the base, but weâre extending out from it.â

Antonio Acquaviva, executive sous chef and head of development Project: charcuterie

âIâm from Italy and the culture is about growing the pig, eating the noble parts at Christmas and turning the leg and shoulder into charcuterie. Whatâs amazing is from the north to the south of Italy, each part of the pig means something really important. In the north they use the middle part of the muscle, culatello; in the middle and south of Italy, they specialise in the neck, capocollo, which is fatty and seasoned with fennel. Itâs a noble part of charcuterie culture.â

Jack Meier, demi chef de partie Project: Fernand Point

âFernand Point had a lot of very famous apprentices back in the day, such as Paul Bocuse and Alain Chapel. They cooked the classics â" lots of truffles and foie gras.

âI read through all of the recipes and there were very few measurements, it was all about feeling and taste â" âroughly this muchâ, âthis much at this time of the yearâ. We have to be a bit more precise now.

âPointâs De La Pyramide restaurant [in Vienne, south of Lyon, France] was one of the biggest three-stars back in the day. It closed down during the Second World War, but after it reopened it was very famous â" Charlie Chaplin ate there. Chef gave me Pointâs book [Ma Gastronomie] â" I need to return it to her, though.â