Chef masterclass: Lucuma meringue by James Wilkins

Having learned classical French techniques in Japan, Bristol's James Wilkins has used his unusual background to create an innovative pâtisserie dish. Michael Raffael reports

In classic pâtisserie speak, "Japonaise" describes meringue with nuts folded into the raw mix. It's part of an international family ranging from French to Swiss to cooked Italian meringues and New Zealand's pavlova. The basic recipe (one part egg white to two of sugar) encompasses so many variations that it's hard to imagine anything new emerging.

That, though, is what Bristol chef James Wilkins of Wilks has done. He's adapted a basic French meringue to include a mixture of lucuma and maca powder that adds a caramel flavour and gives it a pale beige-brown appearance. Working with this base, he makes eggshell-like hemispherical cups.

When he first devised the recipe, he stuck two halves together to make a sphere, filling it with a mousse and sorbet. Now, he's taken his concept a step further, by leaving off the upper meringue shell and replacing it with a white-chocolate caramel lid. Inside it is a banana mousse and a fresh yuzu sorbet. The filling reflects two years' experience as Michel Bras' executive chef, working in Japan.

Planning

• Meringue hemispheres

• Caramelised white chocolate lids

• Toasted oat flakes

• Banana mousse

• Yuzu sorbet

Depending on demand, the kitchen prepares one or two batches per week and assembles the dish to order.

Costing

Wilkins runs a weekday à la carte or five-course tasting menu at £64 and a seven-course £78 tasting menu on Saturday nights. Operating with his wife Christine as a team, he aims for a lower gross profit margin than is common across starred restaurant setting. Food cost at around 40% allows him to use live langoustines, lobster, wild turbot and other ‘noble' ingredients.

Lucuma meringue spheres

The batch size is for about 50 shells, but allow for some breakages during handling. For each 6cm semi-sphere flex-mould, allow about 2tbs of raw meringue.

Note: you'll also need a ladle with a diameter a little smaller that the mould.

Ingredients

50g lucuma powder

25g maca powder

200g egg white

400g caster sugar

Sift the lucuma and maca powder together. Prepare a classic French meringue: whisk the egg whites to soft peaks, add the sugar and continue whisking till the mixture is stiff, glossy and just leaves the edges of the bowl.

Rain in the powders and incorporate them. Let the whisk turn at its slowest speed for a few seconds or the mix will collapse (1).

Fill all the moulds to one-third with the raw meringue (2). Use the ladle to smooth it around the edges (3). Dry out the meringue overnight in an oven at 50°C-60°C (4).

Pare away any rough edges around the rim. Store in a sealed container until service (5).

Caramelised white chocolate lid

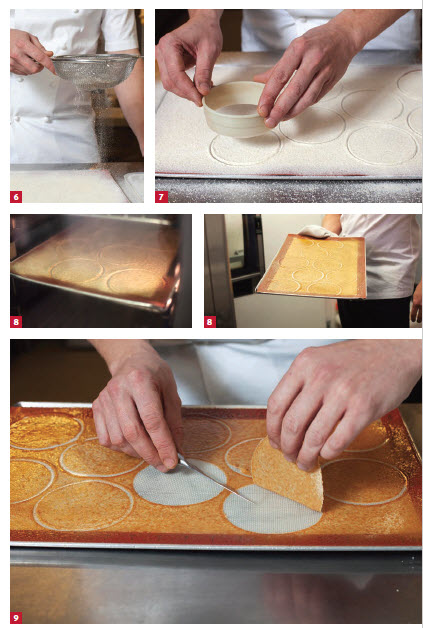

The preparation is similar to making tuiles. Work with 50cm x 30cm baking sheets and silpat mats. You'll also need the same 6cm moulds used for the meringues.

Batch size: 675g (makes around 60)

500g fondant

500g glucose

200g white chocolate pistoles

Preheat the oven to 180°C (low fan). Boil the fondant and glucose to 155°C. Add the chocolate, let it dissolve and mix it in. Empty onto a mat and cool until it's sticky. Blitz in a food processor and pass through a sieve to obtain a crumb (6).

Spread a fine layer of the caramel over the silpat mat. Cut 8cm x 10cm discs from each prepared tray (7). Bake for three and a half minutes (8).

Invert the moulds on a work surface. Let the tuiles cool for a few seconds, lift them off the mat and shape around the mould (9). Leave to harden.

Note: because the caramel hardens fast, you will have to return the tray to the oven from time to time to keep the discs pliable.

Banana mousse

Work in batches based on 500g of peeled bananas to make around 1.4kg (30 portions)

500g peeled bananas

1-2tbs lemon juice

5 soaked and squeezed gelatine leaves

100g egg yolks

240g caster sugar, approx

340g crème fraîche

400g double cream

Put the peeled and roughly chopped bananas and lemon juice in a vac-pack. Cook for 20 minutes at 84°C. Empty into a Thermomix and, while still hot, incorporate the gelatine, egg yolks and sugar. Sieve, transfer to a mixing bowl and cool.

Before the banana base sets, fold in the crème fraîche and the lightly whipped

double cream.

Yuzu sorbet

Quantity is for one Pacojet canister

500g clementines

1 whole yuzu

100g sugar

50g glucose

Lucuma meringue sphere, banana mousse, caramelised white chocolate, fresh Japanese yuzu sorbet

For 1

Grated yuzu zest

Yuzu coulis

40g-50g banana mousse

1 lucuma meringue semi-sphere

1tsp toasted oat crumble

1x40g-50g scoop yuzu sorbet

1 caramelised white chocolate lid

Dot a little coulis around the plate (about 25g) (10) and then sprinkle a little grated yuzu zest around the dots (11). Pipe a teaspoon of mousse onto the centre of the plate. Stand the meringue on the mousse (12). Pipe the rest of the mousse round the inside of the meringue shell to form a nest (13). Sprinkle with toasted oat crumble (14). Scoop the sorbet from the canister and lay it in the centre of the meringue (15). Fit the white chocolate lid (16).

To drink

Christine Wilkins recommends Gewurztraminer Zinnkoepfle Vendanges Tardives from Léon Boesch: âgolden, honeyed, with walnut notes that match the banana and yuzu flavours.â

Lucuma and maca powders

Healthfood stores tout these powders, both of Andean origin, as superfoods, but James Wilkins uses them for flavouring. Lucuma is a pulpy stone fruit, picked at ultimate ripeness, dried and powdered; it tastes of caramel but without the cloying sweetness, and is a pale beige colour. Maca is a Peruvian root vegetable, a sort of bulbous parsnip, with a similar non-sweet, caramel, vegetal flavour.

Yuzu

The chief characteristic of fresh yuzu is that itâs bitter like a Seville orange and perfumed like the most perfect clementine, with a grapefruit back-taste. UK chefs often buy it in bottles. When processed like this, it makes an adequate product, but comparing this with the fresh fruit is like comparing Tetra Pak orange juice to the freshly squeezed kind â" thereâs a loss of quality. The fruit is native to China, but chefs automatically link it to Japan. Its exotic nature means that top-quality juice attracts a heavy premium around, about £10 per 100ml.

James Wilkins waits until the harvest in mid-autumn and then imports it fresh from Japan. A yearâs supply, 15 kilos, costs him £550. Heâll use it fresh until Christmas, then use grated zest, frozen juice and yuzu vinegar made from the pulp till the following season.

James Wilkins

With little fuss and less fanfare, James Wilkins has been building up his Redland Bristol restaurantâs standing. The one-time executive chef of Michel Brasâs Toya restaurant in Hokkaido, Japan, he has a pedigree thatâs very different from the current generation of chefs who have worked their way up through the kitchens of high-profile British ânamesâ.

He was 27 and working in London when he decided he wanted to gain more experience in France: âI wrote to every three-Michelin-starred chef in France â" a total of 26 letters translated into French by a friend who was pastry chef where I worked. I received three replies: two said no thanks, the other was a voicemail from the head chef of Michel Bras saying come over and heâll give me a trial.

âI went over and got thrown on the sauce section for a full Saturday evening service on my own. The chef who normally ran the section was another English guy who was leaving. He explained a bit about how it all worked and they offered me a job to replace him.â

After spending three seasons in Laguiole (the restaurant closes in winter) and the rest of the year in Paris, Monsieur Bras invited Wilkins to go to Japan. There he ran the 55-seat restaurant, staffed entirely with Japanese workers, except for a French maitre dâ.

âIt was the middle of nowhere, with lots of fresh and foraged ingredients â" fantastic for fish. Rather than ceps weâd use matsutake mushrooms. The Japanese really love the food of Michel Bras because itâs so much lighter than most French cuisine.â

At the end of his two-year contract Wilkins planned on returning to open a restaurant in the UK, but Britain was in the early throes of the 2008-2009 financial crisis, so instead he moved to Istanbul and took on the kitchens of Gaja in the Swissôtel.

âTheyâd just spent several million on a roof terrace and on refitting the restaurant, so it was a good package and basically I was saving money until my wife Christine and I had enough to open here.â

What drew him to Bristol? âWhen you look at places for sale in England, the vast majority are pubs and it wasnât really my style. We wanted a restaurant.

We wanted the freehold because I didnât want the risk of a bad landlord. Once we whittled it down, there were only five or six options in the whole of the south of England. Bristol stood out from everywhere else, so six years ago we took the plunge.â

His timing has, he believes, been lucky: âIt was the beginning of a big noise about food in Bristol. A lot of well-trained chefs were coming in. Previously, they were guys who had never left town, so they had limited experience even though they were running decent places. Now youâve got people whoâve travelled; theyâve worked in London or France and they have more knowledge and experience: Jan Ostle at Wilsonâs is a great English Bistro; George at Bulrush has just won a Michelin star, plus many others. There are four one-starred restaurants in Bristol now, when a few years ago there was only one.â

Each has its own style. Wilkinsâ own combines spontaneity, changing his menu daily to include whatâs best with standout ingredients that give a special zing. Yuzu is a case in point.

âItâs in season now for just one month. Weâll be using it in various ways in both sweet and savoury dishes â" grating it over a tartare of scallops, for example, with fresh English wasabi. It doesnât even put the zest on a plate â" itâs just the oil spraying onto it â" but as an aroma, thereâs nothing like it. We will use it fresh until Christmas, then weâll freeze it, zest, juice and pulp it, and continue to use it in other ways throughout the rest of the year.â

Every chef cooking at a high level is, he believes, the sum of their past experiences.

âItâs very difficult to put a âflagâ in food these days. French, British, Japanese, Italian, modern or classic, we do all these things in one way or another because thatâs our training.

âMy various suppliers and markets decide the best quality, seasonal ingredients for the day and I just add my experiences. I cook the market every day. Whatâs important to me is that what we serve is an authentic reflection of what I think good food is â" no chasing trends, no copying others.â

So itâs up to his customers to decide on the style or what is unique about his cooking, not him.

A new leaf: a lettuce masterclass with Lisa Goodwin-Allen >>

Masterclass: Chantelle Nicholson uses aquafaba to create a kohlrabi starter >>