Chef masterclass: pâté en croûte by Calum Franklin

Calum Franklin, executive head chef of the Holborn Dining Room at the Rosewood London, demonstrates his take on a French classic. Michael Raffael reports

These evolved into the pâtés still popular in France today. Their recipes have changed very little and reflect an era when the technical knowledge was notches below what it is now. The pastry is unnecessarily thick, often bland, and cooking times are unnecessarily long.

What executive head chef Calum Franklin has done at the Holborn Dining Room, within the Rosewood London hotel, is put every aspect of pâté en croûte under the microscope. He has challenged accepted wisdom and devised a recipe that matches current tastes.

Equipment and preparation

You will need a hinged Matfer Bourgeat pâté en croûte tin, 30cm x 8cm x 8cm, non-stick with ridged sides. Brush with softened butter rather than a spray, because sprays wonât allow the pastry to stick as well to the ridged pattern.

Prepare a template â" cardboard or similar. Open out the hinged tin and lay it flat. It will be 46cm long, including the flaps at each end, and 24cm wide. Cut out a template that is 25mm wider than the edges on either side of the tinâs base and 25mm longer than the flap at each end. The template will be 51cm long and 29cm across the waist.

For rolling you will also need a large (650mm x 450mm) chopping board. Either place in the freezer or chill thoroughly before use.

Planning

Holborn Dining Room prepares five or six pâtés as a batch. Advance preparation includes: making the filling; making the jellied stock; and preparing and freezing the cylinders of foie gras and duck breast running through the centre of the pâté.

Make the batch of pastry, vac pack and chill in rectangular blocks. When forming the pâté, rapid chill it or place it in the freezer between steps. After baking, chill and leave overnight before adding the melted jellied stock.

Costing

Depending on the filling â" duck, rabbit, game â" the pâté costs upwards of £20 for 12 portions. It sells in the restaurant for £11. Itâs very labour intensive and a batch, spread over the preparation time would, according to Franklin, be at least a dayâs work.

For the pastry

Makes 6 terrines

3kg strong flour

60g evaporated milk powder

120g table salt

1kg unsalted butter

12 whole eggs

2.7 litres whole milk

60ml cider vinegar

Sift flour and milk powder and add to a stand mixer with salt. Add the butter and mix until a crumble texture has been reached.

Beat eggs with milk and vinegar and add to mixer and combine briefly until the dough is formed (do not overwork).

Split the dough into vac pack bags of 1kg weight. Flatten out and seal, then chill for at least two hours before use and for no longer than two days.

Inserts

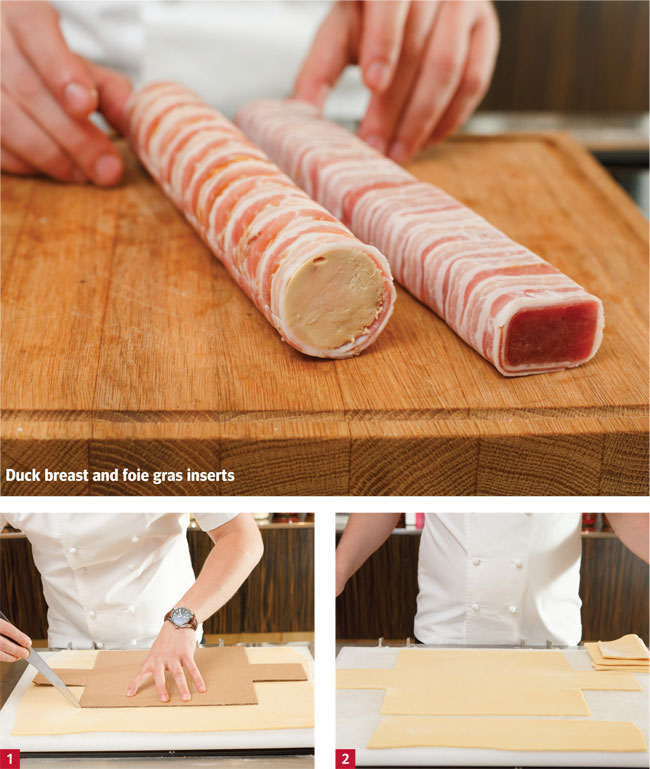

For Franklinâs duck pâté there are two inserts: duck breast and foie gras, frozen to maintain shape in pâté building and also to help keep the breast pink while cooking. For this reason it make sense to make batches of the inserts so you are not making them every day.

For a batch of 12, brine six lobes of deveined foie gras for minimum of 18 hours in 2.75kg salt, 2.75 litres water, 2.75 litres milk and 45g butcherâs salt. Rinse and pat dry and then cook at 30°C for three hours in a water bath with a little vegetable oil in the bag to prevent it sticking.

Remove foie gras from bag and reshape in cling film in cylinders of 3cm diameter by 30cm length and chill until hard. Then remove the cling film and wrap again in thinly sliced raw pancetta and roll once more in cling film and freeze.

For the raw breast insert, remove breasts from three ducks, trim off the skin, fat and fillets and retain for farce. Remove all sinew carefully and cut breasts in half lengthways. Set in a long narrow 500mm pâté mould lined with cling film, topping and tailing the thinner and thicker parts of the breast to keep even down the length. Freeze solid. Remove from the mould and carefully trim up the sides to get a perfect rectangle, retaining any trimmings for farce mix. Cut into 28cm lengths and then wrap each rectangle in thinly sliced pancetta, roll tightly in cling film and return to freezer.

Filling

Each pâté needs 1.5kg. Mince the leg meat, liver, heart, tongue and any fat round the parsonâs nose from the three ducks, 2kg pork shoulder, plus trim retained from making inserts. Mix in 35g salt, 20g butcherâs salt, 40g white mustard seeds, 200g chopped, peeled pistachios, 300g of 1.5cm diced lardo and 20g picked thyme. Weigh this mix into the 1.5kg portions and vac pack ready for use.

Rolling and cutting out the pastry

Lay the kilo block of pastry dough on the chilled and lightly floured chopping board.

Roll out, keeping the rectangular shape until it almost covers the board. It will be 3mm thick and about 60cm x 45cm.

Lay the template as close to the bottom edge of the pastry (the edge thatâs closest to you) (1). There will be a strip about 10cm wide left for the lid and four smaller pieces that will be used for the âchimneysâ (2).

Lining, filling, sealing

Check that the mould has been thoroughly buttered. To fit the pastry in the tin, fold in the flaps at each end. (3) Fold each of the long sides (4) and then in half again (5) so that the pastry will drop neatly in the tin. Unfold the pastry along the side and let it drape over the edges of the tin (6). Unfold the two ends and let them drape over the ends of the tin.

Press the pastry into the ridges of the tin (7). When doing this, press in a downward direction. Transfer to the freezer for 10 minutes.

Divide the minced filling into three equal parts. Spread one part in an even layer in the bottom of the pâté (8). Unwrap the frozen foie gras insert and press it firmly in place down the middle (9).

Fill the gaps on either side of it with pieces of the second part of the filling (10) and cover the insert with the rest.

Unwrap the duck breast and fit it on top of the farce down the middle of the pâté. Cover with the third part of the farce (11). Smooth the top so it forms a neat dome over the top (12). Transfer to the freezer for 10 minutes.

Lay the strip of pastry reserved for the lid over the filling and nick the corners for a neater finish (13).

Crimp the pastry hanging over the edge of the tin to the pastry lid (14). Franklin creates a wave effect by pressing the edges together with the index of the left hand and lifting the edge of the pastry with the right hand.

Glazing

Glaze the top with beaten egg yolk. Donât brush the crimped edges yet. Transfer to the freezer for 10 minutes.

Cut parallel ridges in the top for decoration. Make four holes for the âchimneysâ. (15)

Eggwash the top again, including the crimped sides. Cut out four 3cm rings and make holes in them with a pen or similar (16). Brush with egg yolk and fit them over the holes in the top of the pâté. Fit the foil funnels into the holes (17).

Baking and jelly

Preheat a convection oven to 185°C. Bake for around 45 minutes to a probed temperature of 55°C. Take out of the oven and leave to cool.

Carry-over cooking will bring up the temperature to 68°C.

Chill overnight so the farce has had time to shrink a little and leave you space to add the jellied stock. Remove the foil funnels from the top of the pâté. Using a squeezy bottle, pour the jellied stock through the holes (18). The pâté will need about 250ml altogether.

Foil funnel

Jelly for duck pâté en croûte

Fold a rectangular sheet (about 30cm) of kitchen foil in half along its length and then in half again. Cut into four equal lengths. Wrap the foil rectangles around a pen or similar to make hollow tubes.

Jelly for duck pâté en croûte

For a batch of jellied stock, brown the three duck carcasses and pork shoulder bones in the oven. Roast four carrots, two onions, one leek, one celery and half a head of garlic in a pot, add 300ml red wine and 300ml Madeira and reduce by two-thirds. Add the bones, 30g thyme and top with 1 litre veal stock and water to cover. Simmer for three hours while skimming. Pass and then reduce to 1.5 litres.

Season, then bloom 12 leaves of silver gelatin in cold water, melt into stock and set aside.

Calum Franklin

Calum Franklin traces his love affair with pies and pâtés en croûte to July 2016. The building housing the Rosewood London in High Holborn is over a century old and he discovered a cache of antique pie moulds in a basement store. He recalls: âIt occurred to me that Iâd never used this kind of equipment before. I donât like having gaps in my knowledge of cooking, so I asked whether anybody in the kitchen had any experience of using these things and nobody had.â

If he wanted to plug this weakness, he would have to teach himself. It took him three months of trial and error to crack a pâté en croûte recipe that satisfied him.

Information online or in books was scant. French chefs, typical of the old school tradition, were secretive about sharing their knowledge. He believed their attitude led to stagnation. âPeople donât progress. Somebody will come up with a version thatâs very good and itâs admired, but thereâs no motive for them to push it any further.â

His approach is the opposite: âThe more chefs in the UK making pâtés en croûte, the more we have to challenge and improve what we are doing. Competition is the healthiest thing to have in the industry and you need to embrace that with abandon or fall behind.â

When they were in fashion at the end of the 20th century, there was a spurt of inventiveness, influenced by molecular cooking and a Scandinavian influence, before they drifted off menus. The biggest impact, Franklin argued, was the change in kitchen environments: âThe majority of restaurants that open have five or 10 in a brigade and itâs much harder in those environments to have the time. Itâs a very involved process.â

At the Holborn Dining Rooms he has integrated âpiemanshipâ into the structure of his brigade. The Pie Room, which opens this month, will have a permanent sous chef and two commis working three-month terms: âI train the sous chefs, they train the next step of chefs. It filters down so that one day the young chefs starting their career now will be able in the future to pass on the knowledge.â

Although he emphasised taste over look, design also plays a key role in the creative process. âIf I ask a sous chef to produce a new pâté, Iâll tell him to go away and think about what we already do, make sketches, come up with something original and, most importantly, to not look at other peoplesâ work.

Thatâs how we forge dishes that are recognisable as being from specifically our restaurant. We work within our own design guidelines but still with creativity.â He insists on the quality of his produce. âFor the amount of effort that goes into these dishes, we are going to honour that with the right produce. It adds to the level of respect that the chefs apply in the process. We spend our money on what we think is important, so that will always be a better quality of meat or fish instead of a scattering of edible flowers.â