Fairtrade fortnight: How to make your mark

Increasingly ethically-aware consumers still look for the Fairtrade logo and operators should know that the mark signifies both a product that is produced fairly and one that tastes good too

Fairtrade products might well be a money-maker this year. A survey last year said internet searches for Fairtrade-marked products had dropped; and yet, with the hospitality sector locked down, Fairtrade products in retail grew 13.6%. This, said research house GlobalData, was because one-third of consumers became more concerned about sustainability and ethical sourcing during the pandemic.

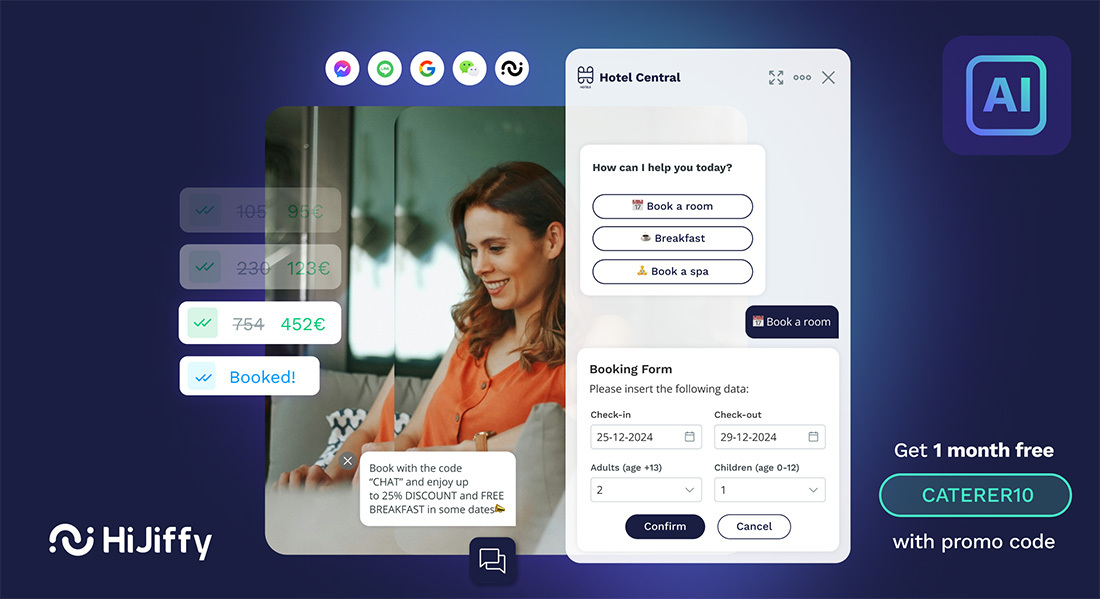

So the trade’s puzzle for this year is whether promoting Fairtrade Fortnight, from 28 February, will be a profitable business move. In theory, hospitality can achieve great Fairtrade-friendliness: 11 years ago, the Max Havelaar Foundation of Holland advocated a hotel room in which everything was Fairtrade-marked, from the mini-bar items to the chocolate on the pillow, the cotton used in the soft furnishings and in staff uniforms, the flowers and the cotton buds. Even the in-room accessory sets of sewing kit, vanity kit and shower cap were Fairtrade. In response, the Australian hospitality industry retorted that such ideals achieved only 1% of Fairtrade sales in its country, and remained a headache to source. They still are.

The best Fairtrade sales always come from food and drink, and so do the new opportunities – one this year may be the avocado, the ‘green gold’ export, which is so important to Mexico that the drug cartels became involved and some avocado exports go to the border under armed guard.

“We’re seeing opportunities for the first Fairtrade avocados in the UK,” says Will Browning at the Fairtrade Foundation. “Out of home is our potential growth – 42% of consumers don’t think restaurants communicate the sustainability of their food enough, and Fairtrade can play a role in this. Our hospitality focus has always been on coffee and tea and sugar sticks, but we now have more active conversations around wine, fruit and vegetables.”

Typically, the major Fairtrade item at Fuller’s pubs is its Brewer Street house coffee. “It is difficult to decide which standard to adhere to,” says head of sustainability Oliver Rosevear, “but with items such as coffee, people do expect us to source certified products. In the wider drinks offer, Fairtrade products are less common than organic, particularly with wines.”

And yet, the on-trade is the big target for Fairtrade wine. These have always done best in retail, but all brands say their aim now is acceptability in the hospitality trades. Even the People’s Choice Wine Awards now has a Drink Fairtrade class.

Grape expectations

Fairtrade wines come from Argentina, Chile, Namibia and Lebanon, but the most active are the South Africans. “Our Fairtrade wine has always been of high standard, and it’s getting better annually,” says Anthony Van Schalkwyk, sales manager at Bosman Vineyards. “Our vine nursery can track our wines right back to the ‘motherplant’, and our aim is to build a Centre of Excellence.

“Restaurants prefer wines that do not compete with retail. Trade business changed when restaurants were unable to open their doors and there was a huge shift to dining at home – but now, there isn’t a better time to tell restaurant guests how good South African wines can be.”

The South African Stellenrust Wine Estate won Fairtrade accreditation 14 years ago, and has kept it ever since.

“We are one of the few South African Fairtrade wineries that can produce five-star wines, and we have one of the biggest and most successful staff empowerment projects with Fairtrade accreditation,” says cellarmaster Tertius Boshoff. “We were the first winery to produce official Olympic wines, for London 2012, and they were both Fairtrade.

“Our Kleine Rust Fairtrade wines are only destined for on-trade sales, as they are distinctly crafted to fit all kinds of foods. The range is honest quality in the bottle at generous prices, making it competitive – we only need sommeliers to taste it and they will do the promotion for us.”

Trade suppliers agree about the quality. “We have supplied Fairtrade wines for over 10 years, the quality is consistently good and customer loyalty is excellent,” remarks Jon Woodriffe of Origin Wines. “It’s part of the overall buying decision for a proportion of wine drinkers,” confirms Neil Palmer, founder of Vintage Roots.

There are also some Fairtrade spirits: Oxfam in Belgium has sourced Paraguayan rums, and the first Fairtrade vodka was French. Jameson recently put the mark on its ‘Irish whiskey-based coffee spirit’, a limited-edition cold-brew drink. But many other spirits and liqueur makers use the term ‘fair trade’ very freely, and not all products are Fairtrade-accredited.

Certainly, coffee is catering’s biggest Fairtrade item – Bewley’s reached 25 years of Fairtrade work last year, and UCC generated more than a million pounds in Fairtrade premium funds. The revenue from Puro Fairtrade coffee by Miko has grown the brand’s own managed rainforests to more than the combined size of Britain’s top 100 natural parks.

Still, few operators bother promoting Fairtrade coffee, maybe because its old poor image has stuck. Some corporates reluctantly buy it because they have to – as one noted roaster remarks: “Sustainability is a box to be ticked off in the cheapest and easiest manner possible.”

But Fairtrade coffee quality is now high, say others. “Quality is much better than before,” remarks Marco Olmi, managing director at Drury. “Just before lockdown we created Astraea, which no customer can pronounce. It’s a very nice blend of top-quality Fairtrade Colombian and Brazilian, and this is gaining traction. I’m expecting rapid growth for it this year.”

Do customers want it?

“Awareness of Fairtrade is at a record high,” says John Steel, chief executive at Café Direct. “The pandemic put a lot of focus on what matters to us, and Café Direct’s work has had a monumental impact – nothing matches the effect of smallholder farmers, face-to-face, thanking you for making the impossible, possible. This is what good business is about.”

It is worth explaining or ‘selling’ what goes behind your ethically-sourced coffee, agrees Jeremy Torz of Union Coffee Roasters: “What sits behind the tick-box is not well understood. Yes, consumers see that producers get a ‘fair price’, but not what this means in real terms for communities. An increasing number of growing hospitality brands are now looking to partner with a roaster such as Union, who really knows the detail of ethical sourcing, to give them a story to sell to their customer.”

Agreement comes from former Fat Duck chef Ashley Palmer-Watts, now director of the relatively new Artisan Coffee. His trade sales are ‘rolling out nicely’, but he says operators must make more of the story: “A lot of chefs don’t know much about coffee, only a minority of the public do… and some people think ethical badges are a load of rubbish, while others place a lot of trust in them.”

This is true, says Lincoln and York: “Fairtrade has an important role to play and this will continue,” says commercial director Ross Schofield. “In our recently developed Ready to Buy House Range, the vast majority is Fairtrade-certified. Consumers are expecting the best and a logo they recognise can only help hotels and restaurants sell the benefits of what is an otherwise unrecognisable corporate social responsibility [CSR] supply chain.”

Stamp of approval

Fairtrade is increasingly a minimum-level sourcing requirement for CSR, remarks Guy Wilmot at Bird & Wild. “What you believe in is reflected in the coffee you serve, whether in little vegan/hippie indie cafes or in big corporate offices. Bird & Wild, the RSPB’s official coffee, also has 100% recyclable packaging – these are things the foodservice operator can use beside the Fairtrade logo in their point-of-sale marketing.” Smaller independent labels using the Fairtrade logo include the Land Girls, run from a smallholding in Rutland. “We source from selected farms and producers to be fair for the women who produce them,” says founder Emma Brown. “Typically, this is a women-led co-operative in Sumatra.”

Clipper was the first British Fairtrade tea brand, and has paid £4m in Fairtrade premiums. The mark is still relevant, says impulse controller Adam Perry.

“Many tea drinkers do care about it, and if it’s important to consumers, it should be important to operators, too. Some of our trade customers stock Clipper so they can say they serve ‘the most ethical tea around’, and make a profit in a fair and sustainable way. We’ve now developed point-of-sale materials for the hospitality sector that help bring this to life and show all the great things about Fairtrade that not everyone knows about.”

How Fairtrade should be referred to on a restaurant wine list or coffee menu is also important to think about. It must be there, say suppliers, but perhaps not with the Foundation’s own promotional designs, which tend to be more suited to schools and churches than a classy tea lounge. “The truth of all this is, it matters a lot to some people, and there are enough of them to be worth your while making a serious feature of it,” says Olmi.

“On a good coffee menu, the words ‘Coffee, Fairtrade’ and the logo are not nearly enough – but to say ‘this is a Fairtrade coffee, we chose it, and we can tell you about the farmers who produce it’ means that you have given yourself the option of talking about it and really selling it.”

What is Fairtrade and the Fairtrade mark?

Fairtrade is a system of certification that aims to ensure a set of standards are met in the production and supply of a product or ingredient. For farmers and workers, Fairtrade means workers’ rights, safer working conditions and fairer pay. For buyers it means high quality, ethically produced products.

The Fairtrade mark is a registered certification label for products sourced from producers in developing countries. The mark is used only on products certified in accordance with Fairtrade standards and on promotional materials to encourage people to buy Fairtrade products.

A business that wants to create a Fairtrade product can apply for a licence to use the mark. All uses of the mark and marketing to promote Fairtrade products must be approved by the Fairtrade Foundation.

Photo: Thinglass/Shutterstock.com