Pot of gold: how do chefs raise funds for Bocuse d'Or?

Taking part in chef competition the Bocuse d'Or, while a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for many chefs, is hugely expensive, with the ingredients

alone racking up thousands of pounds. Vincent Wood takes a look at how competitors are funded

When it comes to a food spectacle, there is possibly nothing bigger than the Bocuse d'Or, the Olympic-style biennial championship of cuisine in Lyon, France, established by Paul Bocuse in 1987. A vast audience roars, bangs drums and blasts horns in scenes seen at no other culinary competition, while some of the greatest talents in cuisine produce monstrously opulent platters for a judging panel made up of some of the greatest chefs on the planet. It is vibrant, passionate and louder than life. It is also colossally expensive.

When Team USA won in 2015 under the guidance of the French Laundry's Thomas Keller, it was accompanied by a funding push that reportedly ran into the millions. While no country has taken gold as many times as host nation France across the competition's history, Norway, Sweden and Denmark have taken up more podium positions than mainland European and Asian countries combined.

Asked by BBC News last month if the competition's Scandinavian supremacy came down to the region producing more creative chefs, UK team president Simon Rogan hit back at the assertion: "No, not really. They're creative chefs, of course, but they've got the budget. It's not really a level playing field."

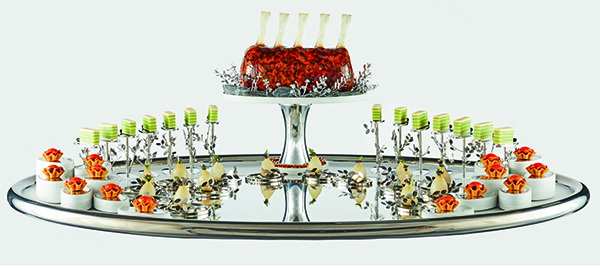

The platters alone can cost tens of thousands of pounds, while the specific, high-end ingredients required to compete - sometimes available from only one source - must be repeatedly bought for candidates to train with on the two-year journey to the competition. Different countries deploy different models: the US pools vast sums of private and corporate investment; last year's winner, Denmark, along with other Scandinavian countries, lean on state funding.

Team UK chairman Andreas Antona, chef-patron and owner of the Cross at Kenilworth and Simpsons in Birmingham, has the task of gathering the British contingent's resources. He told The Caterer: "Hungary, for example, gets direct government or regional government support. They see it as an important aspect of planning for their tourism industry. They like to sell their country via food."

Without state support, the UK turns to the industry to sustain the Bocuse team. As well as paying for equipment and travel, the chefs who take part sacrifice their time, which would otherwise have been spent working, so Antona ensures the candidate, the coach and the commis take a salary from the Bocuse pot. "If they've got mortgages, they still need to pay them - that's where the money goes," he says.

Rare beasts

But support expands beyond money. When Tom Phillips, head chef at London's Restaurant Story, competed in the European heats in Turin, he was asked to produce a platter centred around a fillet of Piemontese beef. The task of sourcing and supply fell to butchery supplier Aubrey Allen; its relationship with the team began in 2010 after it engaged with then-candidate Simon Hulstone, who had called for more support for Team UK.

Simon Smith, the director of customer relations for the firm, met with Hulstone in the Hinds Head in Bray almost a decade ago to set out a path for the future of the team. He says: "From that point, and from that day, the candidate has shared the technical spec with Aubrey Allen. We've taken on a role to get that meat element to the specification of Bocuse d'Or so that the candidate can practice on the product in order to give them the best possible chance. Since then, we've seen things like Swedish suckling pigs and Hungarian venison and blue leg chicken. It's been quite a challenge."

In return, sponsors get the prestige of association with the world's greatest chefs and the chance to build up an international reputation among their client base. Smith adds: "The bigger picture is that I believe that cuisine in the UK is going from strength to strength - and I see that when I travel - but it does need an international platform to showcase how well we are doing and to create a buzz. I think we've seen that with the Scandinavian teams and how well they've done. By supporting this, more guests are going to come to the restaurants in the UK, which in turn translates into orders and this helps suppliers.

"We believe we are the best in the business here in the UK," says Smith. "And you have to surround yourself with the best people, the best like-minded chefs and the best suppliers. And that's what Bocuse gives us."

Big wins

Across the Atlantic international cutlery and crockery manufacturer Steelite began to fund the US team after building a relationship with Keller, setting the nation on a path that would see Mathew Peters become the first American to take gold.

"It was incredible. We had participated for two Bocuse series prior to 2017 and it was great to be one of the sponsors involved in the victory," says the firm's chief executive John Miles. "It was an awful lot of hard work and dedication by the team members and the executive team that culminated in a win and it was terrific to be a small part of it."

Beyond the spectacle, the relationship between business and contestant allows firms to reinvest in skills that filter down into fine dining kitchens the world over, in training and techniques that spread across brigades and in the national pride of a cuisine. For outliers like the UK team, which has never ranked higher than fourth, the competition can be one of proving the worth of the country's cuisine.

Both Antona and Rogan describe winning the competition "as putting your two fingers up at people" who doubt British cuisine and "trying to help the UK throw off this image of having shit food".

For the US, the impact of the victory was palpable - a clear indicator of the evolution of US fine dining in the eyes of the world under the likes of Keller. Miles adds: "We've always looked at ways to try to give back and mentor the US organisation.

Bocuse d'Or has two primary roles: one is funding a team to participate in the global competition, but the second is reinvestment into skills for the participants in the industry.

"Helping to fuel the team to represent cutting-edge culinary trends was a very big deal for us and something we wanted to participate in. But the mission of reinvestment back into people also coincides with our own mission."

Investment is just part of the picture - after all, the US invested heavily in the 2019 competition only to come ninth, one place ahead of the UK's Phillips. However, on the road to Estonia for the 2020 European heats and back to Lyon for the final in 2021, the fight for gold will continue to rage behind the balance sheet as much as it will behind the pass.

Search for sponsorship

Team UK has been sponsored by the likes of Valrhona, Urbani Truffles, University College Birmingham, Mauviel 1830, Ritter Courivaud and Aubrey Allen. To join them, please contact Anne-Sophie Labruyere at as.labruyere@goustation.com or call +44(0)7794 969363.