Masterclass: Paneer kofta and quinoa pulao by Manish Mehrotra

Manish Mehrotra is taking traditional Indian cuisine and adding his personal touch, as well as a fine dining edge. Michael Raffael reports

Kofta, paneer and pulao are familiar words to anyone who goes to Indian restaurants, whether they are cheap and cheerful eateries or at the Michelin-starred end of the dining spectrum. While Manish Mehrotra hasn't rewritten the rulebook for these dishes, he does take the bones of the classic preparations and updates them.

His quinoa pulao, for example, isn't baked or part-steamed in a sealed pan, and his fried kofta dumplings have as much tofu as curd cheese. It's one way of reinventing a cosmopolitan style of Indian fine dining. But that isn't all he does.

He describes the way he develops his dishes as "layering flavours". Every element in a Mehrotra dish has a taste echo or ties in with the others. The onion-tomato chutney can be found in the kofta and there are dabs of it on the finished dish. Together (and carefully balanced) they create a sense of harmony that makes each mouthful part of the whole.

Indian cookery is about blending spices. His contribution is to stick to basics like garam and chaat masalas, and then adapt them to the style of plate service we associate with the middle and upper echelons of restaurants.

Time magazine recently included Delhi's Indian Accent in its list of the top 100 destinations in the world. Its New York outpost, opened in 2016, and it does 200 covers a day.

Fay Maschler, grande dame of restaurant critics, gave the London operation five stars. A handful of chefs have built mini-empires on the strength of a flagship restaurant. What has worked for them is also working for Mehrotra. He has developed a repertoire that has his personal touch, but it's also replicable and adaptable, from the basic preparation of the spices to their impact on the plate.

Paneer kofta, quinoa pulao

Note on batch sizes: the three restaurants serve different numbers and have different sized kitchen brigades: 13 in London and 30 in New Delhi. Quantities here relate to the London operation.

Planning

- Make the garam masala, usually once a week

- Make the chaat as basic mise en place

- Prepare the onion-tomato chutney

- Cook the quinoa

- Make the kofta balls ready for frying to order

- Finish the pulao during service

- Fry the kofta to order and plate

Costing

Three courses: £55; four courses: £65; six courses: £85. Menus are designed so hat customers can compose their meals from any items.

Onion-tomato chutney sauce

Quantities here are for the photos. Scale up as necessary. It's used in the pulao, the kofta and as part of the final dish.

- 25ml neutral oil

- 2tsp garam masala

- 1tsp white urad daal

- 1tsp curry leaves

- 1 pinch asafoetida

- 100g onion, finely diced

- 100g tomatoes, chopped and seeded

- 30g tamarind (slightly sweetened with jaggery)

- 1tbs coriander leaves, chopped

- Salt

Heat the oil and fry the garam masala until fragrant. In quick succession add the uncooked daal and curry leaves (1). Sauté for a few seconds and then add the asafoetida. Lower the heat and add the onion and tomato (2). Sauté till the onions start to soften. Stir in the tamarind and cook out the sauce for three to four minutes. Mix in the coriander leaf (3). Blend and add salt to taste (4).

Note: For the final stage of the recipe, retain a little in a small piping bag.

Quinoa pulao

The base for six portions: 250g washed quinoa, boiled in 750ml salted water and drained. Then, for two to three portions:

- 20g butter

- Pinch cumin

- Pinch of diced fresh ginger

- 1tbs onion-tomato chutney

- 2tbs boiled petits pois

- 1tbs coriander leaves

- Salt

Heat the butter in a frying pan and add the ginger and cumin. Stir in the onion-tomato sauce and the petits pois (5). Cook out for a couple of minutes and stir in the coriander. Cook for around a minute more and season. Mix in about 120g cooked quinoa and blend it thoroughly with the base (6).

Paneer kofta

Quantity for six kofta balls

- 250g fresh tofu

- 250g paneer

- 30g ghee

- 1tsp cumin seeds

- 1tsp ginger, diced

- 1tsp green chilli, finely sliced

- 3tbs onion-tomato chutney

- 2tsp chaat masala

- 1-2tsp coriander, chopped

- 1tbs Cheddar, grated

- tempura flour

- Panko crumbs

- Frying oil

Grate the tofu (7) and squeeze out most of the moisture through muslin (8). It will lose about half of its weight. Grate the paneer and mix with the tofu.

Heat the ghee and fry the cumin, ginger and chilli until they sputter. Stir in the onion-tomato chutney and cook for two or three minutes (9). Add the chaat masala and coriander, stir in the Cheddar and work the mixture until smooth (10).

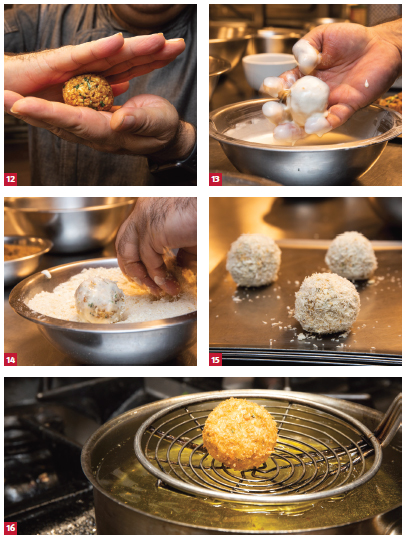

Cool and then form into six balls (11). To make each one, roll about 40g of the kofta between the palms of your hands (12). Dip each ball in batter to coat it completely (13) and then roll it panko crumbs (14) and chill (15). Fry the kofta balls to order.

Assembly and plating

Serves 1

- 1 paneer kofta ball

- 80g approximately quinoa pulao, reheated

- 1tsp onion-tomato chutney

To garnish

- Curry leaves, deep-fried

- Micro-leaves

- Lotus seeds, dusted in chaat masala

Heat the oil to 180°C. Deep-fry each kofta ball until it is a light golden colour (16) and then drain on absorbent paper. Put a 10cm diameter hoop in the middle of a plate. Spoon the pulao into it and flatten it. Cut the kofta ball in half and put the two halves on the pulao, cut-face up. Pipe a dab of the onion-tomato chutney on each one. Remove the hoop. Stand a fried curry leaf on each half and finish with micro-leaves and lotus seeds (17).

Manish Mehrotra's garam masala

Indian Accent in London makes about 2kg of garam masala – roughly a week's demand – at a time. Put all the ingredients in a 1/1 or 2/1 gastronorm pan.

Roast for 15 minutes at 150°C in a convection oven. Cool and blend to a powder. Every chef's bespoke recipe for this differs. Here, the emphasis is on the

perfumed spices:

- 300g coriander seeds

- 300g cumin seeds

- 100g fennel seeds

- 200g black cardamom

- 300g green cardamom

- 200g mace

- 100g cinnamon

- 100g star anise

- 200g rose petals (buds)

- 100g bay leaf

- 200g black pepper

- 100g cloves

Chaat masala

The seasoning powder is familiar enough in the UK to be on some supermarket shelves. But what are the key ingredients that give it its specific taste? The faintly sulphurous note comes from black salt. Used sparingly, it's just identifiable and balances the other ingredients. Mango powder brings a hint of sourness and dried mint adds an imperceptible herb note. Other ingredients may include pepper or dried chilli and ajwain.

Makes around 500g

- 75g cumin seeds

- 70g black peppercorn

- 75g black salt

- 35g dry mint leaves

- 10g asafoetida

- 25g ajwain

- 150g dry mango powder

- 60g ground ginger

- 20g yellow chilli powder

Manish Mehrotra

Eighteen years ago, Manish Mehrotra was cooking in a members' only restaurant at Habitat World, India Habitat Centre, operated by Old World Hospitality in New Delhi. Much has happened since then. As corporate chef of Indian Accent Restaurants in New Delhi, New York and London, part of Rohit Khattar's Old World Hospitality empire, he's injected a sense of finesse to a cuisine that has often relied on taste rather than appearance.

Building on the runaway success of the Delhi operation, he's opened in two key cities – London and New York – over the past four years. Each brought its own challenges.

"When we opened in America," he recalls, "we were a bit scared, because we didn't know how we'd be received. New York has very few fine dining Indian restaurants. In London, we moved into the space previously occupied by the group restaurant – Chor Bizarre. Here, people have a reference point for comparison, whether it's with Gymkhana or Benares, even though our food is completely different from what they do."

Neither location, he admits, has customers as demanding as those in Delhi, though.

"People know everything about Indian food there. They recognise the flavours. They know about regional dishes. Their palates are educated about spices from childhood. But they also want something different from what they eat daily."

Despite having a reputation for creativity, he isn't, he insists, seeking to devise new tastes.

"My cooking is about taking traditional flavours. I don't tinker with the spice levels if I'm in London or America. It's a misconception, for instance, to assume we like chilli-hot dishes. Thai cuisine is much hotter than ours."

What matters is the blending of spices and adjusting their quantities to individual dishes. As an aside, he points out that he would never use raw coriander leaves, because he finds them soapy. Instead, he cooks them along with other ingredients, in the same way that a European chef might use thyme or rosemary.

Learning how to blend is an acquired skill, rather than one that's taught. "I was brought up in a vegetarian household. My father never ate onion or garlic and there was no question of eating meat or fish. So, in my house we knew that without these, food could be made delicious with the help of spices. That idea was always there."

It isn't true, he argues, to say that Indian cooking is only about its spices. "Sometimes you eat a dish and the spices are in your face," he points out. "When I cook I want people to be able to taste the flavours of all the ingredients. My aim is always to create a harmony. When I talk about layering I mean that you can taste all the ingredients, you can experience them in relation to each other and you can taste them in different parts of your mouth."

Given his international success and 23 years' professional experience, is he tempted to open a restaurant of his own? "No, I'm not. If I had my own restaurant I'd be a businessman and I wouldn't be a chef any more. I am happy being a chef. Old World Hospitality is home to me."