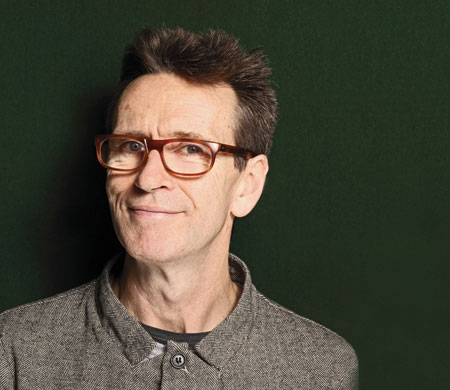

Oliver Peyton: the perfectionist

Restaurateur Oliver Peyton is not so much a master of reinvention as an expert in evolution, or as Jason Atherton described him: "a visionary". Janie Manzoori-Stamford talks to the Great British Menu judge about his future plans and his obsessive attention to detail

He opened a string of restaurants under the group name Gruppo, including the wildly successful Atlantic Bar & Grill off Piccadilly Circus (the space is now home to Corbin and Kingâs Brasserie Zedel), Coast in Mayfair and the particularly tricky â" and frequently robbed â" Mash and Air bar and British/Italian restaurant complex in Manchester.

It was during this period that Peyton worked with some culinary luminaries during their formative years, including Jason Atherton, who was sous chef to Stephen Terry at Coast before taking his first head chef position at Mash and Air; and Bruno Loubet, who spent time as a development chef for the group before helping Peyton launch Isola/Osteria dâIsola in Knightsbridge.

But the early 2000s saw his star begin to fade. Stiffer competition, changing demographics and the geographical obstacle of operating in London and Manchester all took its toll, and the closure or sale of Peytonâs restaurants were the result.

However, the new millennium also saw a new direction for Peyton emerge. In 2000 he took over the catering at the Somerset House museum, where he ran French restaurant the Admiralty, and his event catering company Gruppo Events took care of the takeaway deli, summer café and corporate hospitality â" a business he later sold for £3.6m to Compass Group in 2002.

Peytonâs comeback was sealed two years later when he partnered with the Royal Parks Agency to launch Inn the Park, a 200-seat British-style restaurant and café in St Jamesâs Park, and shortly after he founded Peyton and Byrne with his sister Siobhan Peyton (Byrne is their motherâs maiden name).

There followed another string of new openings, but this time within some of Britainâs most treasured national institutions and public spaces. Recent additions to the portfolio include the Brighton Dome and Royal Pavilion, the Imperial War Museum London, which Peyton and Byrne will operate from June following a major redevelopment of the museum and café space by Foster + Partners, and the Keeperâs House, the companyâs second food and drink space at the Royal Academy of Arts in Piccadilly.

At the same time, the company has continued to grow its retail side of the business, with branded bakery/café operations popping up in the likes of the British Library, Kew Gardens, St Pancras railway station and, most recently, Wellington Street in Covent Garden. And through all of this, Peyton has cultivated a media career that kicked off after he was asked to be a judge, alongside Prue Leith and Matthew Fort, on the BBC series Great British Menu back in 2006.

FUNDS FOR GROWTH

Peyton is not so much a master of reinvention as an expert in evolution, or as Atherton described him recently, âa visionaryâ. A decision to seek investment from the government-backed Business Growth Fund (BGF) (Peyton and Byrne secured £6.25m at the tail end of 2012) came as part of a focus on taking the business to the next stage of its development.

âWe had come to a point in the company where we were funding things through cash flow, a bit of bank lending, a bit of lease purchase,â he explains. âBut when a company gets to a certain size, its ability to grow hits a glass ceiling. Our issue wasnât money â" it was growth. We needed to grow quicker, but when you do, the capital requirements get bigger, and it couldnât be done without the funding.â

In addition to the sought-after cash injection, the BGF provided Peyton and Byrne with expertise and advice that was not readily available within the family business, and also offered a welcome alternative to private equity â" a funding route that Peyton was reluctant to follow.

âWe are not in a rush to sell the company or do anything like that,â says Peyton. âThe BGF is a long-term player and itâs happy for us to grow the business. It brought gravitas to our company and I canât recommend it enough.â

Shortly after the investment was secured, Peyton and Byrne announced a seven-year contract to operate all restaurants, cafés and bars at Brighton Royal Pavilion & Museums and the Brighton Dome. Part of the £20m deal was a promise, made possible by the cash injection from the BGF, to invest around £600,000 in a staged refurbishment of the facilities, which began last March.

The contract was also the firmâs first foray outside London, something Peyton says he was in no rush to do, having been âburnedâ in Manchester with Mash and Air, which closed in 2000. Despite having Atherton in the kitchen, the location of Mash and Air proved too much of an obstacle. Not only was the restaurant complex too far from the rest of Peytonâs operations in London to be practical â" âit takes time to go there; it takes hours out of your day,â â" but its position within Manchester attracted an unwelcome trio of âguns, drug barons and organised thuggeryâ, Peyton recalled with disappointment 18 months after it was sold.

Nowadays, Peyton lives up to the bon vivant moniker through his work, friends and beloved family, rather than the indulgence and excess he was known for in the heady 1990s, so no doubt thereâs some relief that the challenges the company faces in Brighton are a lot less hairy than his last business experience outside the capital. Operating at music venue Brighton Dome instead offers a different type of challenge, especially after such a long run of museums and galleries.

âIâve become slightly obsessed with getting people to eat before concerts as part of the experience,â Peyton says. âWeâve got a concert hall, a beautiful venue and we can cook food. I canât see the difference between selling a concert ticket and selling a food ticket. But itâs still early days. I would say that a contract in a place like Brighton is going to take two to three years."

POINT OF PERFECTION

The expansion of Peyton and Byrneâs bakery business is a major part of the companyâs growth strategy, and with it comes a concerted effort to perfect every single element of its offer, which suits Peytonâs obsessive attention to detail. He doesnât want his outlets to just serve coffee â" he wants them to serve excellent coffee, as good as anything in those âcool, beardy typeâ operations.

The food offer has come under the same scrutiny, with a firm emphasis on making sure everything is fresh. The companyâs sweet and savoury development chefs, Glyn Gordon, who was previously pastry chef at Simon Roganâs LâEnclume, and Tom Catley, whose background includes Ottolenghi and Nobu, have worked hard to ensure all the cakes, muffins, pastries, bread and sandwiches are fresh.

The sandwiches, for example, are made in smaller batches and remain at ambient temperature because, Peyton insists, if you spend two hours making fresh bread, then make it into a sandwich and put it into a fridge, it sort of defeats the object. But reaching the stage where these ambitions could become reality was far from easy.

âIt took a long time to get it right. We opened up and then I realised it was a lot harder than I first thought. But itâs much easier to control stock when youâre not putting it in the fridge. We judge how many we need to make. If someoneâs got to make more, weâll make more.â

The complicated nature of the operation is what convinces Peyton that he hasnât created a cookie-cutter concept that he can now simply roll out, but plans are afoot to open a further three or four bakeries over the next 12 months, starting with a Greenwich outlet thatâs already in the pipeline. Sights have been set on opening in another train station, as well a couple more in Londonâs West End, thanks to the confidence that comes from having the right team in place.

Training will play an integral role in the companyâs success, and Peyton recognises that itâs not the key players that are the problem. The competition for good staff in hospitality is notoriously fierce, thanks to an ever-present skills shortage, so 2014 will see the introduction of a comprehensive training programme at Peyton and Byrne that will work from the ground up.

âThe people that are seen by the customers is where the hard work is,â he explains. âWe need to motivate them and keep them happy. Weâre going to put in place a super-duper training programme this year that will give people a real gastronomic career path in the company. I have to create an environment in which people want to come and work, and also where career-orientated chefs see an opportunity to become famous.â

Peyton says heâs never shied away from anything because itâs hard, and this attitude is evident in his ambitions to not only be the best, but to consistently be ahead of the competitive curve. He has renewed vigour for the business and this has made him want people to come from around the world and say: âWow â" what Peyton and Byrne do is world classâ.

âIâm not interested in plodding on. I have been in restaurants for all of my adult life and I have stuff that I can share with young people. Whether itâs right or wrong, Iâve been there. So thatâs what I want to do really. I feel good about restaurants at the moment â" I feel quite inspired. Iâm going through one of my âthe tablets are workingâ phases,â he laughs.

GREAT BRITISH MENU

Oliver Peyton has been a judge on the BBCâs Great British Menu alongside Prue Leith and Matthew Fort since the series started in 2006.

Great British Menu is now in its ninth series. What is the theme for 2014? Itâs about the D-Day landing and it takes inspiration from what happened then and the food that was around during the Second World War. We have D-Day veterans coming on to judge with us. Itâs amazing â" the people are great. This one is a real privilege to be involved in.

How have the chefs found the brief?

The chefs have really done a bonkersly good job. The impression I get from a lot of them is that being involved in this has been a bit of a spiritual journey as well. They met people who are really quite old now and who gave up a lot for their country. The chefs had to do a lot of research about the way people lived, what they went through, what they had to give up, and all the things that surrounded that. It had a lot of personal impact on them and how they felt about the food.

There were a lot of complaints that the brief for last yearâs Comic Relief-themed series was too vague and therefore difficult to judge. Do you think thatâs fair? Iâve got to be honest with you: a lot of us felt it was a slightly missed opportunity. Sometimes the brief needs to be a lot narrower, but weâd all talked about it being freer and letting the chefs go crazy. Thereâs all this technology around for food, so we were thinking pacojet, foams, colour⦠theyâre all going to have a great time. In the end, that really wasnât the case.

Why do you think that was?

You can be the best chef in the country, but if your idea isnât good, youâre not going to get through. They all know that. And while an idea might be really great, if it doesnât deliver on the palate, it wonât get through.

Chefs all have dishes that are their stock in trade, so they want to use them in some way and decorate the plate in the manner that suits the show. Thatâs what I would do, because the most important thing is winning, right? Thatâs what happened in the Comic Relief one, but the people that got through were the ones that didnât do that and instead delivered on both levels.

How did you get involved in Great British Menu in the first place?

I asked myself that on the first day: âWhy am I here? Is this candid camera or something?â I got involved because they asked me. I was really quite shy because it was Prue Leith and Matthew Fort â" and they know stuff â" but the funny thing is, after a while, you realise that you know stuff, too.

Is it good for business? I canât say whether it is or not. I never thought, when I was 17, coming to England, that Iâd end up doing a food TV show in my 40s and 50s. The most interesting thing about television is no one gave a damn about my opinion prior to being on it. Now all of a sudden everyone thinks Iâm a bloody expert! Itâs really weird how you go from zero to hero. I think: âWhy werenât you interested in my opinion before?â

What have you enjoyed most about Great British Menu? The greatest thing to come out of the show is the food producers. What no one understands is most producers get up in the morning, they talk to their animals, they milk them, they grow their veg, they till the field, they do whatever they do, and they donât meet another human being. Great British Menu showed them that there was lots of potential to produce things that were premium products they could sell to the public.

No one has really given chefs enough credit for going out and talking to farmers and telling them they should be growing rocket, or doing this type of tomato, or those brassicas. What about chard? Where was chard 10 years ago? A lot of that comes out of chefs talking to the farmer directly.

Vegetables are the new thing now and the quality of vegetables just in the last two years has sky-rocketed. You can see that next year itâs going to be even better still.

How do you think Great British Menu has affected the chef industry? Iâm benefiting now from having young chefs who had other career choices they could have made, but theyâve watched the show, and theyâve seen that, actually, itâs quite interesting. Itâs not all rubbish and people arenât stabbing each other every five minutes. âOh look, heâs a nice personâ, or âOh look, thereâs a girl â" I can become a chefâ â" do you know what I mean? All those things have happened as a result of it, and itâs brought a lot more people into the business.

THE KEEPERâS HOUSE

Peyton and Byrne opened the Keeperâs House, its new restaurant at the Royal Academy of Arts, Piccadilly, last October

Launching a restaurant in a museum or gallery comes with a very strict timetable, usually dictated by the exit of the previous operator, the close of one exhibition and the launch of another, or both. When Peyton and Byrne took over the Restaurant at the Royal Academy in 2011, it was given the kitchen on the day it opened.

âWe opened to some blockbuster, so the doors opened, people flooded in and it was almost impossible to recover,â remembers Peyton. âAll of my friends who run high street restaurants will say âweâre opening up next month; come in and tell us what you thinkâ. I forget what itâs like in the real world.â

But the launch of the Keeperâs House was a very different experience. There were 18 days between the close of one show and the start of the next, and the opportunity to get in and get it right is clearly evident, from the David Chipperfield interiors that incorporate pieces of academiciansâ art, to the ingredient-led menu, created by head chef Ivan Simeoli.

âIvan is one of my babies,â Peyton beams. âIâve got three or four chefs who Iâve been working with for some time, who Iâm trying to develop into long-term chefs for the business.â

The Keeperâs House and Simeoliâs food were quick to attract the attention of the critics. While the reviews were largely positive â" Jay Rayner described Simeoliâs cooking as one of the galleryâs best-kept secrets, while Fay Maschler called the Keeperâs House a âpolished West End havenâ â" there were those that remained unimpressed, with pricing in particular coming under fire. Does that bother Peyton?

âIâm sort of old enough now to take it all in my stride,â he says. âThere was a time when reviewers really knew bugger all about food and just liked the sounds of their own voices, but now I think a lot of them have a really great understanding of food. If you donât listen and take action, then youâre going to fail anyway, arenât you?â

So while Peyton is insistent that there will always be a premium attached to the prime ingredients that his restaurant uses, prices have been and will continue to be monitored and adjusted accordingly to ensure a proper sense of value is achieved.

âIf people leave my restaurants and feel they didnât have value for money or a good experience, then I havenât done my job properly,â insists Peyton. âItâs very important to me personally that this is a good restaurant. And I think it will be. I feel really good about it.â

OLIVER PEYTONâS RESTAURANT HISTORY

Atlantic Bar & Grill â" 1994 to 2005

Coast â" 1995 to 2000

Mash and Air, Manchester â" 1996 to 2000

Mash â" 1998 to 2008

Isola and Osteria dâIsola â" 1999 to 2004

The Admiralty at Somerset House â" 2000 to 2002

Inn the Park, St Jamesâs Park â" 2004

The National Dining Rooms and National Café at the National Gallery â" 2006

The Wallace Collection â" 2007

ICA Bar & Café at the Institute of Contemporary Arts â" 2008

The Orangery and the Pavilion at Kew Gardens â" 2010

The Restaurant at the Royal Academy of Arts â" 2011

The Keeperâs House, Piccadilly, London â" 2013

Brighton Dome and Royal Pavilion â" 2013

Imperial War Museum, London â" contract won 2013, opens June 2014

BAKERIES

St Pancras â" 2007

The British Library â" 2009

Central St Giles â" 2010

Victoria Gate Café at Kew Gardens â" 2010

White Peaks Café at Kew Gardens â" 2010

Wellington Street â" 2013

Â