Root cause: Moor Hall's Mark Birchall creates a carrot masterclass

Mark Birchall is taking fine dining further. The Moor Hall chef elevates humble ingredients, such as the carrot, with a variety of techniques to form a satisfying whole that still possesses the distinct qualities of the original vegetable. Michael Raffael explores

If logic dictates that chefs should handle all ingredients with the same care, it follows that carrots deserve as much respect as, say, lobsters. Something of that mindset lies behind Mark Birchall's ‘Baked carrot', a layered dish of tastes, textures and techniques and the first course served to guests in the dining room.

Together, the elements of the dish represent a daunting collection of steps and processes. Taken individually, they lie within the compass of most modern chefs' know-how. Each element poses and answers the question: how to add maximum taste.

The impact lies in welding the parts to form a satisfying whole. It's a garnish-free recipe. Yes, it looks good; yes, there's a nod to molecular theatre when freeze-dried cheese snow falls onto buttered carrot spikes; and yes, it plays with textures and mouthfeel. But it doesn't take customers out of their comfort zone.

Planning

• Carrot juice and dehydrated carrot slivers are part of basic mise en place.

• Seasonal buckthorn berries, bought fresh, are frozen and processed for juice and oil.

• Freeze-dried Doddington cheese powder is made in batches to match service needs and stored at -20°C (minimum).

• Hazelnut pesto is made in batches and chilled.

• Carrot purée, prepared on the range with fresh carrot and juice, is used both in the plated dish and the carrot tuiles.

• Sea buckthorn dressing is part of the plated dish and also used to rehydrate carrot slivers.

• Carrots (large and small) are slow-baked on top of the range in butter and salt ahead of service and served warm.

⢠Cheese powder is sprinkled over the plated carrots in front of the customer.

Costing

As a restaurant with rooms, Moor Hall in Aughton, Lancashire, only sells its seven suites (from £195) to customers dining in the restaurant. The £125 menu includes four tasters, taken in the bar, and eight dishes served at the table, including cheese and three desserts.

Birchall aims at achieving a 70% gross profit on the menu, but it's currently at 68%. Raw materials for the baked carrots are relatively inexpensive, but other courses may include caviar and truffles.

Freeze-dried Doddington cheese

Doddington is a hard, unpasteurised cheese, produced in Northumberland.

375g water

1.5g agar

1g salt

8g citrate

Nitrogen

Melt the cheese with the water. Simmer gently for 30 minutes (1). Stir in the agar, salt and citrate (2) and chill over ice to a creamy, dropping texture (3). Empty into a large bowl or pan. Pour liquid nitrogen over the cheese (4). Break up the frozen solid mixture with a rolling pin or similar (5). Transfer to a Thermomix and blend to a powder (6). Store in a fresh container and reserve in the freezer (7).

For service at table, put about three tablespoons per customer in a chilled bowl or pan and sprinkle over the carrots.

Hazelnut pesto

80g toasted hazelnuts

25g Berkswell cheese (similar to aged Manchego), grated

350ml pomace oil

1tbs pickled ransom seeds [see note]

Chop the parsley in a Thermomix or similar. Add hazelnuts, cheese and oil and blend to a loose paste. Hand-chop the pickled seeds and stir into the pesto base (8). Chill thoroughly so that the mixture thickens (9).

Note: the wild garlic seeds are picked in late spring, lightly salted, left for about a week and then preserved in a light vinegar.

Serves 10-plus portions 400g sliced carrots

200ml carrot juice

Salt

Simmer the carrots in the juice very slowly on the range until the liquid has almost completely evaporated and the carrots are very soft (10). Blend in a food processor and season (11).

Carrot tuiles

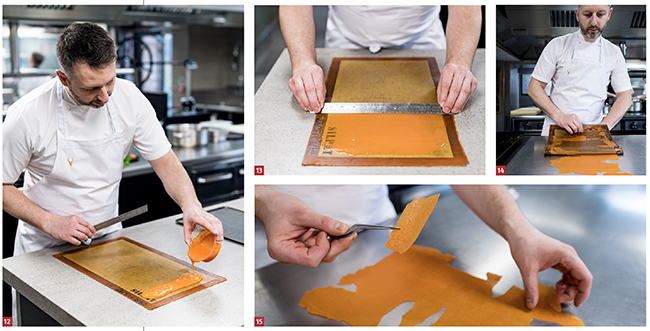

The carrot purée above is also used to make the carrot tuiles. The Moor Hall kitchen will prepare about 10 Silpat mats' worth of tuiles at one time.

Empty about 150g of the carrot purée onto a Silpat mat (12). Use a ruler to coat the mat with a thin film of purée (13). Recover the excess purée that has spilled over the edges and use for the next mat.

Dry out the sheets of carrot overnight at 65°C. To remove the dried carrot from the mats, turn the mats upside down onto a work surface while still hot. Peel off the carrot (14). Break into shards and store in containers with silica gel (15). Allow about three shards per serving.

Dehydrated carrot

Carrot slivers are dehydrated to concentrate their flavour and then rehydrated with buckthorn juice and carrot purée (16).

Batch size: allow about 24 dried carrot ribbons and multiply as necessary 24 slivers dehydrated carrot

200ml 50:50 buckthorn juice and carrot juice

Vacpack the carrot with the juices and steam to soften them. Repack them in portions of three to four, together with the juice. Seal and water-bath them six hours at 80°C.

The carrots

The aim is to combine different colours and sizes: round, slender, tapering and chunky. Each portion, though, needs at least two thin, steeple-shaped carrots to give height.

In the Moor Hall kitchen, large and small carrots cook together in a large pot. When the small ones are tender, they're taken out, while the large ones continue cooking. Fresh, organic carrots don't need scraping or peeling.

Serves 8 40ml rapeseed oil

200g salted butter

16 long, thin carrots

3-4 large carrots

Optional: small round carrots

For service, cut off the thin carrot bottoms so the tops stand upright. Cut the large carrots into bite-sized chunks.

Sea buckthorn berry oil

Sea buckthorn is acid and the oil should absorb the fruitiness of its flavour without the bitter or sour quality.

Steam vac-packed buckthorn for two minutes. Repackage it with an equal weight of neutral rapeseed oil. Cook the oil overnight in a water bath at 75°C. Cool, and when the oil and juice have separated, strain off the oil.

Sea buckthorn dressing

Serves 20 300ml sea buckthorn juice, steamed and extracted with a juicer

Sugar and salt to taste

1.5tsp xanthan gum

Season the juice and stir in the xanthan (start with a dry spoon) to thicken it to a light coating texture.

Deep-fried pearl barley

This adds an element of crunch, so it's more than a garnish. Boil 100g of pearl barley until tender. Drain, dry and dehydrate. Deep-fry for about 20 seconds at 180°C. Allow a small pinch per serving.

Baked carrot Serves 1 2-3tsp hazelnut pesto

2-3 ribbons of rehydrated carrot slivers

1-2tbs sea buckthorn dressing

3-4 button-sized dabs of carrot purée

Pinch deep-fried pearl barley

2 thin carrots (warm)

3-4 carrot pieces (warm)

3-4 shards carrot tuiles

1tsp sea buckthorn oil

Microleaves: chrysanthemum, carrot and purple chard

2-3 tsp Doddington cheese powder

Spoon most of the pesto onto the centre of the plate (18). Arrange carrot slivers coated in dressing on top (19). Use a squeezy bottle to pipe dabs of purée around the pesto (19). Stand the thin carrots in the middle. Arrange carrot chunks coated in dressing around them. Add the carrot tuile shards.

Finish with a few spots of sea buckthorn oil and the rest of the pesto. On the pass add the microherbs (20), and finish with more dressing and sea salt.

Send to the table. Snow Doddington cheese over the carrot in front of the customer (21).

Mark Birchall

Moor Hall's chef-patron Mark Birchall wants to "make a Mecca for good food". It is a carefully chosen sentence, with âfood' as distinct from the signature, fine-dining cuisine that has earned him a couple of stars in 19 months. He's as enthusiastic about the pressed cheese he's started making in his microdairy, or the in-house charcuterie, or the microherbs grown in a Victorian lean-to greenhouse, as he is about any dish on his £125 set menu.

And he has plans on the horizon: a bakery and a microbrewery. Last year, he opened a second restaurant, the Barn, in the converted farm building alongside the 16th-century manor that houses the restaurant with rooms.

That vision, setting aside his passion for Lancashire and its produce, has a practical edge. He's aware that he's in the north west. He isn't in a major city, even though Liverpool is close and Manchester a 45-minute drive away: "You have to create something special for people to travel to. I'm not saying this is a one-stop shop, but it's more than a luxury restaurant."

His road to Moor Hall has had three career-forming staging-posts. At the turn of the millennium he cooked under the legendary Franco Taruschio at the Walnut Tree in Abergavenny: "It's where I learned how to season; it's where I learned how to work fast," he says. The next stop, Northcote in Langho, Lancashire, felt, he recalls, like a step up. "It was a very strong kitchen. Nigel [Haworth] was there for every service. It wasn't British food; it was heavily regional. All the cheese was Lancashire. Poultry was from Goosnargh."

During the nine years spent at L'Enclume in Cartmel, Cumbria, he acquired the package of molecular skills that were part of the El Bulli-inspired trend. In parallel, Simon Rogan was developing his farm. "Dishes became more plant-based, but without shouting about it," he recalls.

Birchall has tried, he insists, to translate aspects of his past experience into Moor Hall. To these he would add the three months spent in Spain at El Celler de Can Roca, where he went as part of winning the 2011 Roux Scholarship: "It was ultra-creative, but they always cooked dishes they believed in."

What he aims for in his cooking is clarity of flavour, however complex the preparation may be: "If you put a carrot on a plate with some sea buckthorn and garlic and cheese, you want to taste those flavours."

Some of his recipes do, he concedes, involve multiple steps, but others (he cites a black pudding shell stuffed with pickled gooseberry) are quite simple: "What matters more is the level of care, whether it's the ingredients or the cooking."

He doesn't want customers to think they are coming to eat a tasting menu. "We want them to feel at home, to relax and enjoy themselves. As soon as you walk through the door, you feel like you're being looked after. You don't have to think too much."

It's a significant shift of emphasis for high-end dining. Birchall wants customers to visit Moor Hall for the total hospitality experience, rather than a brush with the cuisine of a high-profile chef. And to return again and again.

Chef profile: Mark Birchall at Moor Hall >>