From Marco Pierre White to the modern chef era – the dawning of a new, collaborative approach

It’s been more than three decades since Marco Pierre White emerged as the most enthralling British chef of his generation. But now it seems less likely that anyone will become his modern-day successor. The age of the towering culinary genius might be over, but Andy Lynes reckons something more exciting, accessible and collaborative has replaced it

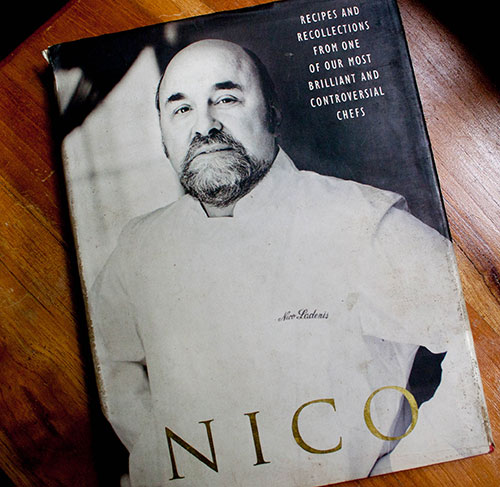

Whatever happened to the heroes? When The Stranglers asked this legendary line in their 1977 single No More Heroes, vocalist Hugh Cornwell was, of course, referring to Leon Trotsky, the great Elmyra and Sancho Panza in his original lyrics, but if he ever fancied updating them with a culinary spin, he could substitute names like Marco, Nico and Koffmann. Because no chef in Britain has emerged in the past 20 years that has dominated the UK’s restaurant scene quite like those legendary figures did in their heyday. Feared, revered and imitated, a small group of chefs in the late 1980s and early 1990s defined their gastronomic era in a way that hasn’t been managed since.

Marco Pierre White

Fay Maschler, the London Evening Standard restaurant critic of 40 years, wrote: "In his recently published book 1971: Never a Dull Moment: Rock’s Golden Year, David Hepworth claims that year as the annus mirabilis for rock and pop music." On Twitter, someone swallowing this premise asks if there is a restaurant equivalent. Quick as a flash, I reply: "Yes. 1987, the year Marco Pierre White’s Harveys, Simon Hopkinson’s Bibendum, Ruth Rogers’ and Rose Gray’s River Café and Rowley Leigh’s Kensington Place all opened."

Although the London, and UK, restaurant scene has changed beyond recognition since 1987, the opening of the establishments mentioned by Maschler (and perhaps, even more importantly, Alastair Little’s eponymous Soho bistro two years earlier) constituted a revolutionary change in the dining scene in Britain, and one instigated by British-born chefs rather than the French, Swiss or Italian cooks that had dominated the high-end scene until then.

Michel Roux

Acceptable in the 1980s

Broadly speaking, before the mid-1980s, the dining public’s options amounted to identikit bistros, trattorias, curry houses and high-street Chinese restaurants (the Roux brothers, grand London hotels and mavericks like Franco Taruschio at the Walnut Tree in Abergavenny and Joyce Molyneux at the Carved Angel in Dartmouth excepted).

Partly because of the relative culinary desert they found themselves in, and partly because they were cooking in a creative and imaginative way with ingredients almost never seen in the UK before, those few chefs were responsible for opening the Pandora’s box of what came to be known as "modern British cooking". Hundreds of hugely talented chefs have opened fantastic restaurants since, but none have changed the British dining scene in quite such a profound and significant way. You only get to open that box once.

At that time, every restaurant opened by empire-builders like White was big news and broke new ground; up-beat designer brasserie the Canteen in Chelsea Harbour was a startling change of direction after the serious fine dining of Harveys, for example. Back then, there might have been a notable new opening every few months. Now, it would be surprising to look at The Caterer’s online news feed and not read about the launch of an exciting new eaterie several times a week, making it much more difficult for chefs to pull focus.

The ‘heroic’ chefs of the 1980s and 1990s actively built mystique around themselves. White Heat is the most iconic cookbook of the modern era. Photographer Bob Carlos Clarke’s stunning black and white shots portray White as a fashionably gaunt rock’n’roll star, brooding artist and smouldering aesthete. White’s words are sneering proclamations of his own genius. When I interview chefs today, I still hear strong echoes of his short, almost Hemingway-esque syntax in their answers.

In My Gastronomy, Nico Ladenis sets himself up as an arbiter of taste, laying down the culinary law on everything from food combinations ("no marriage between two meats, or between a meat and a shellfish or a shellfish and fruit") to the evils of wine snobs.

If Marco or Nico deigned to appear on television, it would usually be in the context of documentary programmes like Channel 4’s Take Six Cooks (although Ladenis did make an appearance on Jim’ll Fix It). White’s disdain for the medium is palpable in ITV’s daytime series Marco that were filmed in the kitchen at Harveys and are available on YouTube.

Tom Kerridge

âThat rivalry was exciting to watch from the sidelines. I think we are unlikely to see their like again, just because the world has moved on. We are likely to see another British three-Michelin-starred chef, but Iâm sure it will be a different type, one that is more media friendly, who understands how to promote themselves and represent themselves and Michelin.â

And that person is likely to come from the ranks of the top chefs that are ready with a family-friendly smile and quip for the Saturday Kitchen camera. In these media-savvy days, few if any chefs would dare to take the combative stance of their legendary predecessors. That doesnât make Sat Bains, Daniel Clifford or Claude Bosi any less of a culinary genius, but it does change the way they are perceived. In the viewing publicâs mind, aloof and tortured has been replaced by affable and easygoing.

Sat Bains

Urbane cool

Chefs no longer seem to have an appetite for that sort of arrogance. The huge increase in competition over the last 30 years has meant chefs need to be much more business savvy. That means less breaking the bank with extravagant plates piled high with luxury ingredients, and more working with the wider chef community to promote the industry.

Chefs cooking at competitor restaurants on guest nights are now an established part of the London and UK scene. Chefs socialise and swap ideas at international congresses like the MAD symposium in Copenhagen and on the national and international food festival circuit â" something that hardly existed in the era of the hero chef. Anecdotes about chefs helping out competitors with emergency supplies and staff, especially for new launches, are common â" but it wasnât always that way.

âI remember hearing a story once of two brigades in London finding themselves in the same venue but they werenât allowed to speak with each other because their head chefs were there â" even though the teams knew each other and some even house-shared,â says Bains, whose eponymous restaurant is a gastronomic beacon in Nottingham.

Claude Bosi

The new openness, however, has undoubtedly led to a degree of sameness. With techniques, ingredients and ideas flowing readily around the chef community, accelerated by the internet, itâs becoming increasingly difficult for chefs to differentiate themselves.

Social media has also had a significant levelling affect. Where once the top chefs seemed unattainable and isolated â" even if you visited their restaurant you might not see them in the dining room â" now everyone has access via Twitter and Instagram. Tweet a compliment to Kerridge on a meal you had at the Hand & Flowers and he might even tweet you back.

âTo compete in the marketplace, accessibility is key,â says Kerridge. âIâve always wanted to be a part of making sure customers feel comfortable. I wanted to take away those boundaries from the beginning. It wasnât about a hushed temple of gastronomy where you have to bow down to the chef â" itâs about having something great to eat and feeling relaxed.â

Daniel Clifford

Partly due to the pioneering work of those hero chefs, good food has now become more geographically accessible too. No longer is it the preserve of a few fine-dining restaurants in Mayfair. The top three restaurants in 2017âs The Good Food Guide â" LâEnclume in Cartmel, Cumbria, Restaurant Nathan Outlaw in Port Isaac, Cornwall, and Restaurant Sat Bains â" are all outside London. Regional restaurant scenes in Bristol, Manchester, Birmingham, Edinburgh and Brighton continue to grow.

Chefs have also quickly learned how to manage their social media profiles in the new era of political correctness, with headline-grabbing online spats with customers and public displays of racy kitchen banter mostly a thing of the past. With his hugely popular Twitter account, Gary Usher of Sticky Walnut has shown that, with the right tone of self-deprecation, itâs possible to be brutally honest about the sometimes harsh realities of the day-to-day life of a chef and still not alienate customers. Usher is a shrewd operator and a brilliant cook, but to his Twitter fans heâs a working stiff with problems just like anyone else.

Gary Usher

Bright young things

The perennial issue of staff shortages, exacerbated by the volume of new openings, has also meant that chefs have had to change the way they behave in the kitchen, putting staff welfare at the top of their agendas. Both Restaurant Sat Bains and Restaurant Nathan Outlaw have switched to four-day weeks, partly to improve staff working conditions.

âWhy make it harder for them?â says Kerridge. âYoung chefs want experiences. Thatâs changing what people want from work. They want the opportunity to visit vineyards and go and see the butchers and visit other restaurants on their days off. They want the experience of staff parties and camaraderie and having opportunities to travel abroad.â

Modern restaurateuring is also not conducive to spreading the notion of chef as culinary genius. Thirty years ago, youâd dress up to the nines and pray Marco didnât throw you out of Harveys before you got to taste his tagliatelle of oysters. Now, a meal might form just part of an evening out and, particularly in London, customers may be as tempted by the latest high-concept launch with a menu of 20 variations of lasagne as they are a chef-led project.

âThirty years ago it was about Marco having three stars, â says Kerridge. âBut now, I have just as much respect for Russell Norman for the way heâs built Polpo because you know the pressures that go into making a restaurant work.â

Customers dining at the brilliant Dairy in Clapham might not even know chef-patron Robin Gillâs name, and thatâs not because Gill isnât supremely talented â" itâs just that his efforts are directed into building a group of restaurants (he also runs the Manor and Counter Culture in Clapham and Paradise Garage in Bethnal Green) that deliver a type of relaxed dining experience based on a cooking style and ethos rather than signature dishes.

Gill is emblematic of a modern style of cooking where simple ingredients are served in a casual way and processes like pickling, preserving and smoking are the star attractions rather than flashy technical preparations of luxury items. To the casual observer, chefs are almost absenting themselves from the plate.

Albert Roux

The contemporary, unstructured style of presentation can mean that dishes look similar from restaurant to restaurant â" not something that can be said about Marcoâs classic feuillantine of sweetbreads. Of course, modern dishes still take meticulous preparation, but in a way thatâs less obvious to diners.

Chefs are often growing at least some of their own food, partly absorbing the role of suppliers and muddying the definition of what it is to be a chef. The skills crisis also has a part to play. With so many new openings and not enough chefs to go round, dishes need to be more simple and therefore head chefs donât get the chance to be seen as culinary artists.

There is also less empire-building by chefs, with investor-led and concept-driven groups taking centre stage. And where chefs are opening a string of sites, they often donât have a homogenous culinary identity. Jason Atherton, arguably the leading chef-restaurateur of his generation, hasnât opened a string of Pollen Street Social clones. His seven London restaurants include Sosharu, a Japanese izakaya-style restaurant and Social Wine and Tapas. The long-term effect is that leading chefs are not building dynasties in their own image.

There are, of course, exceptions. I interviewed Simon Rogan soon after the opening of Fera in Claridgeâs hotel in 2014 when he told me: âI just wanted to be known as someone who made a bit of a difference when I hang up my apron, like the Marcos and the Nicos of this world. They absolutely tore through their decade and left a legacy and I want people to think that about me: that guyâs restaurants were bloody amazing and they set the trend for where we are today.â No one would deny that Rogan has the talent and drive to achieve that. Heston Blumenthal, Daniel Clifford and Sat Bains are also modern heroes to many, albeit ones of a very contemporary caste.

In truth, geniuses are only recognised in hindsight. It may not be too long before we are looking back at the heady days of Michael OâHare at The Man Behind The Curtain, Mark Jarvis at Anglo in Farringdon or Tom Sellers at Restaurant Story and saying that it was the start of something.

Whatever happened to the heroes? Maybe theyâve just been waiting in the wings.

Pierre Koffmann

Enduring legacy

Times may have changed, but Britainâs legendary chefs remain hugely influential and their impact can still be felt on the modern restaurant scene.

Pierre Koffmann, who trained Gordon Ramsay, Marcus Wareing and Tom Aikens, boasts 50 years in the kitchen. He reinvented himself when he opened Koffmannâs in 2010, offering a more affordable version of his three-Michelin-starred cuisine, and he has also become a familiar face on TV from his appearances on Saturday Kitchen. He has no plans to retire when his restaurant at the Berkeley closes later this year, and he will appear as a judge on the new BBC daytime TV series Yes Chef this month.

There is no denying the phenomenal impact that Michel and Albert Roux â" often dubbed the godfathers of British cuisine â" had on creating the modern restaurant scene in the UK when they opened La Gavroche in 1967. The Roux Scholarship is one the most prestigious competitions for young chefs and has helped make culinary stars of the likes of Sat Bains, Andrew Fairlie, Daniel Cox, the executive head chef of Simon Roganâs Fera at Claridgeâs, and Tom Barnes, the head chef of Roganâs LâEnclume.

Raymond Blanc remains an influence at Belmond Le Manoir aux QuaitâSaisons, a kitchen that produces world-class chefs including Ollie Dabbous of Michelin-starred Dabbous and Robin Gill of the Dairy, both in London.

Raymond Blanc

Dig the new breed: the sharing chef

These days, modern chefs are more likely to be in each otherâs pockets than at each otherâs throats. Guest chef nights in restaurants are becoming increasingly popular with the likes of Dan Doherty from Duck & Waffle cooking at Gary Usherâs Sticky Walnut in Chester. Usher himself will cook at Simpsonâs in Birmingham for one night in November, an event that sold out in under three hours.

In London, Robin Gill hosts a regular industry night at his Clapham restaurant the Diary, called Bloodshot Supper Club, where he and a guest chef cook an experimental menu â" Edoardo Pellicano of Portland is up next.

Chefs also get together to raise money for charities such as Action Against Hunger. Earlier this year Jason Atherton staged a âSocial Sundayâ of collaborative lunches across his London restaurant group, including a meal cooked by Tom Kerridge, Claude Bosi, Sat Bains and Atherton himself at Pollen Street Social that raised £50,000 for Hospitality Action.

Dan Doherty

âThis industry has grown and gone from strength to strength â" the more people have worked together, the more we share ideas. Rather than it being about in-fighting, itâs about promotion and growth,â says Kerridge.

For Bains, the sharing, collaborative nature of international culinary congresses, such as Madrid Fusion and Identita Golose (launched in 2003 and 2004 respectively) were an eye-opener. âItaly and Spain were already really forward-thinking then and so open with each other. It made me realise that it wasnât just about my kitchen. It was about British gastronomy as a whole. We collectively had to put Britain on the map. It was a really exciting time for everyone and a bit of a global food movement. It made me understand there was no gain in seclusion.â

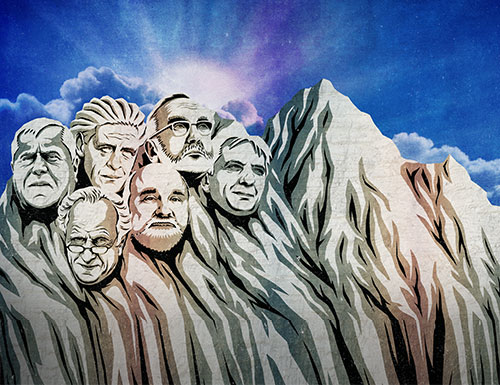

Illustration by Butcher Billy

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â