Bocuse d'Or: Team UK competes at the greatest show on earth

In spite of a Herculean effort and the creation of some jaw-dropping displays of gastronomy, Team UK came 10th in this year's Bocuse d'Or competition, but they are far from despondent. Vincent Wood takes a front-row seat at the greatest show on earth. Photography by Jodi Hinds

Fragrant steam streams from beneath the central cut, a vast veal rib, as the teamâs chef slices into the meat just above the bones. The spectators in the room, so loud they had been approaching jet engine decibels all day, silently wait, watch and â" as the candidate reveals that the flesh inside is perfectly rose-coloured â" erupt into cheers. Sirens blare, horns blast and drums roll to a crescendo as the meat is carved and plated. With the technique and talent of the generationâs finest chefs combined with the atmosphere of a sporting cup final, there is nothing in the world quite like the Bocuse dâOr.

The competition started in 1987 when the late three-Michelin-starred chef Paul Bocuse decided that trade fair the Salon international de la restauration de lâhôtellerie et de lâalimentation â" better known as SIRHA â" could be elevated by a culinary competition. It was to include a live audience (something new for the time, that would evolve from bystanders to full-throated participants as attendees became louder and more organised) and gold, silver and bronze awards. It was around this time that Bocuse, who died in February last year, was accused of watering down his commitment to cuisine by spending less time in the kitchen.

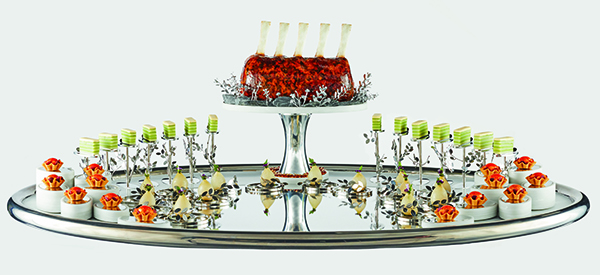

Yet the Bocuse dâOr remains one of his most enduring legacies â" and perhaps the most prestigious competition on the planet. This year the ultimate challenge in cuisine came down to producing two concepts in five and a half hours â" both tributes to great gastronomic losses to the industry in 2018. The first, a chartreuse, was for Joël Robuchon, who passed away in October; the second, a platter of veal in honour of Bocuse. Each comes with their limits: the number of scallops, mussels and other seafood in the chartreuse is meticulously outlined, the cuts of meat are to be presented on the platter equally.

However, it is a competition that always goes beyond the brief, traversing the fine line between incredible food and works of art, the sort of thing that could never reasonably be served in most restaurants, making it an incredible challenge for chefs.

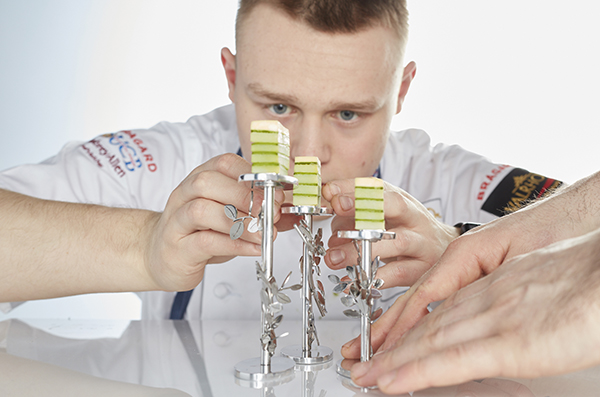

For the 2019 event, the Team UK torch was handed to Tom Phillips of Restaurant Story in London, along with his commis Nathan Lane, previously of the Ritz London.

Phillips is in many ways uniquely placed to tackle the competition. For a start, he has followed the Bocuse dâOr â" which is often overlooked in the UK â" for years, and he has also crossed paths with some of its great alumni. His interest was piqued when he saw the certificate that executive chef of the Ritz London John Williams received for taking part in 2001, and he also worked alongside Matthew Peters at Thomas Kellerâs Per Se in New York when the American chef was building up to his first place victory in 2017.

Phillips says: âMe and Matthew went for coffee just before he was flying out to compete, and he gave me some pointers on what to do. I was going to work in France, but he said I should sack that off and either come and work at the French

Laundry and join the US team, or go back to the UK and be with their team.

âThe first year that I came [to Lyon] was 2017 to support Matt, and itâs the same for everyone â" you come here and you want to be involved.â

The infectious element of the Bocuse dâOr is the unity of paradigm-shifting skill and the electric atmosphere the audience bring to the day. French competitions are always accused of being sticklers for tradition, of calling for nouvelle cuisine above all and not adapting to change. Bocuse dâOr is far from exempt from that, but in reality it is unfounded. The trial is what happens when tradition is allowed to grow into madness â" something awe-inspiring and endlessly loud.

Team coach Adam Bennett holds the title as the closest Team UK has ever come to a podium position, missing bronze by six points in a competition where marks run into the thousands. The chef-director at the one-Michelin-starred Cross in Kenilworth says the competition has always been about pushing the boundaries of the brief as far as they can be stretched, using new techniques and styles to create dishes the world has never seen before and may never see again.

Sound effects

The other revolutionary element of the event is the noise. The chefsâ recipes may be sacred, but the room is no chapel; instead, it has the crackling energy of a football stadium â" something that began the first time Mexico qualified for the final and brought a mariachi band along. The packed audience remains from start to finish, each countryâs supporters sitting in blocks, each with their own unique style of making themselves heard.

At one point roughly 100 Norwegians stand up to shake bells in a wall of sound, while Icelandic supporters begin the thunderclap that has became a signature chant for fans of their international football team. The England supportersâ band â" the very same who cheered the nation through to the World Cup semi-finals in Russia last year â" returns fire and begins to blast brass instruments and smash drums. Denmark, next to the raucous British contingent, let off confetti and wail police sirens through a megaphone. All of this happens at 10.30am, when there are hours still to go, and with nothing to prompt any of it.

Itâs hard to know whether the noise works to bolster morale or distract other competitors. During Team UKâs run, the supportersâ band strikes up a round of âWhen the Saints Come Marching Inâ â" by far the loudest noise in the venue. Phillips, while working through the intricate stencil work of his chartreuse, is nodding along to the beat. âWhen youâre down here doing this and you hear that, it lifts you,â says Bennett as he oversees his two chefs like a conductor, as well as watching some 30 timers on an iPad.

Team UK trained in University College Birmingham, blasting the audio from previous years so loudly that it rang through the corridors. âIf you donât do that you wonât be able to focus,â says Phillips â" but thatâs not to say it isnât motivating. âYou do get into it. Iâve been listening to those bloody songs for the last four months and some of them are quite good.â

The noise isnât the only thing in play as teams look to shake the nerve of their opponents. This year, in the run-up to the final, several teams decided to reveal their garnishes and preparations through Instagram. âIâm sure it got to me a bit, because theyâre putting something out that is genuinely stunning and you know that itâs coming from teams that are going to deliver very well, so I stopped looking,â explains Phillips. âI just stopped going on Instagram, because what am I going to gain from it? Itâs either going to worry me or upset me and I didnât need that.â

He adds: âI joked about it with Nathan, saying I might go and put a square of cheese and a square of pineapple on a cocktail stick and post a picture saying itâs the UKâs garnish. Or just put a big fat Yorkshire pudding on there just to wind everyone up.â

The two chartreuse are plated by each coach â" in the UKâs case, Bennett. Itâs a tense affair as one is presented to the judges and media before being plated, and every second counts. It is also the culmination of not just that dayâs work, but of the two years leading up to it â" from the UK heats to the European heats in Turin, Italy, last year, to this moment. Many coaches, all of them seasoned in their arts and prominent in their nationâs industries, have to gather their composure to stop their hands from shaking as they plate. Team UKâs gets away just in time to not incur a penalty, while the band plays Rule Britannia.

One person that message seems to have struck is Keller, the legendary chef behind the French Laundry, who took his nation from an outlier in the competition to a gold trophy winner. Multiple people at the competition said the chef had repeatedly remarked on the incredible cooking Phillips had produced, telling people inside and outside his team that he simply could not stop eating the food served from the Team UK platter.

At the final ceremony, after two days, 24 platters and 48Â chartreuse, the awards are handed out. Tributes are paid to Bocuse and his legacy, while respects are paid to visiting dignitaries, including a Swedish prince. Ahead of the big reveal, Phillips had said anything within the top 10 would count as a win â" comparing it to his rank in the European heats and noting that, when including some of the top-tier teams from the rest of the world, the UK sat somewhere around 14th.

Gold goes to Denmark and candidate Kenneth Toft-Hansen, who had competed the other side of the kitchen wall from Team UK. All three podium positions are taken up by Scandinavia. Some award winners who fall short of gold skulk up to the podium, seemingly unhappy with their lot. After the confetti and fireworks are done, the full results are released without fanfare â" with tight margins, Team UK are named 10th best in the world, a placing one behind previous winners the US.

Before the results are released, Phillips notes one of the more off-the-wall elements of the competition, an application that, among other things, asked him for his favourite quote. His was âcalm seas donât make good sailorsâ, something that became all the more relevant in the European heats when, due to water pressure issues, Team UK lost the use of their oven for 40 minutes. After keeping a clear head while Bennett furiously rearranged the teamâs schedule, they brought that deficit down to just 15 minutes and qualified for the final.

âGetting through what we went through in Turin I had the confidence to say, OK, thatâs not going to happen in Lyon, but we are going to have other problems for sure. And I know that we got through that, so weâre going to get through whatever Lyon throws at us.â

He thanks his team, his family and the band, who play a last run-through of each of their songs. He praises Toft-Hansen for his win and mulls over the future.

âI said I wanted to be top 10 and weâre 10th,â he says. âIt still has to sink in, really, that itâs over and weâve done it. We have to just take what weâve learned now, improve, come back again and sort it out, get on that podium.â

With the crowd still ringing in his ears, he gives the walls of the venue a decisive thump. âWeâll be back,â he says, before walking back into the crowd, to his team, and to the end of the greatest culinary show on earth.

The England Supportersâ Band

The UK has a reputation for supporting the national team with significant noise â" most of which comes from the England Supportersâ Band, who returned for their first international foray since the nationâs football World Cup in Russia last year.

Band leader and trumpet player John Hemmingham said: âItâs one of the best things we do. People appreciate it and get into the spirit of it all, and the contestants appreciate it too.â

There is, of course, some give and take with the organisers: the five-man band regularly has a supportive spotlight placed on them throughout the day, just in case anyone was unsure as to where the noise was coming from, but it is understood that French culinary titan Regis Marcon is less than keen on the band interrupting his speeches â" so the quintet stay quiet at the appropriate time.

Get The Caterer every week on your smartphone, tablet, or even in good old-fashioned hard copy (or all three!).